Interview by Greg Carlson

Toby Jones is an Emmy-nominated writer, director and cartoonist from Fargo, North Dakota currently living in Los Angeles. He has worked as a writer and storyboard director on “Regular Show,” an executive producer on “OK K.O.! Let’s Be Heroes,” and is the creator of “AJ’s Infinite Summer.”

Greg Carlson: What are your early home viewing memories?

Toby Jones: When you’re a young kid, you don’t really understand why or how movies enter your home. I remember at one point noticing that there was a copy of “The Lion King” in the house. I realized I could watch it anytime, and that was great.

My ritual was renting movies. I walked to grocery stores that rented movies, like Sunmart and Cash Wise. I asked for rides to stores like Take 2 Video. I would call places on the phone and ask whether certain titles were available.

GC: What was the first movie you collected?

TJ: The first movie I made a conscious decision to own was “Billy Madison.” I had rented it so often, I figured I should acquire my very own copy. I said, “Mom, next time you’re at Kmart, if you see ‘Billy Madison’ on video, could you get it for me?” That was the very first time I had a movie of my own.

GC: Mom came through.

TJ: Mom came through. And it was one of the first times I discovered something different on a re-watch. When “Billy Madison” came out on video, I was still a little too young to get all the jokes.

It wasn’t until it got played at a friend’s birthday party that it became the funniest thing I had ever seen up to that point. Watching it so many times made me feel older and smarter as I gradually began to pick up more of the humor.

GC: “If peeing your pants is cool, consider me Miles Davis.”

TJ: Sometimes, I think about doing a fresh, deep dive into the movie with friends, but then I realize it might be painful. Or certainly not enjoyable as it was all those years ago. The age when you first see something is so important.

GC: You had “Billy Madison” on VHS. How much did you expand your VHS collection before making the transition to DVD?

TJ: There were only a small number of things that I cared about possessing at that time. For me, collecting with purpose began with anime. I got into anime in 1999. It was the show “Neon Genesis Evangelion.” I rented the tapes at Comic Junction in Fargo. There were two episodes per tape and it was my favorite thing.

I became such a fan of this show that I realized I needed to have these episodes on hand so that I could study them closely. I mowed lawns so I could save up and buy the collection of “Neon Genesis Evangelion” on video. There were thirteen tapes. Each tape was thirty dollars. So every time I saved up enough for another tape, I would add it to my collection and watch it over and over.

When I had the whole set, I spent one summer with the episodes on loop, so I could find details and pore over fan theories.

GC: So that one series became the gateway.

TJ: Around this time, official anime releases transitioned to the popularity of fansubs and tape trading culture took off. If you lived in a major metropolitan city, you would have a choice of shops and contacts to get your hands on episodes of anime shows recorded from television in Japan that Americans would painstakingly subtitle and distribute — often for free.

In Fargo, those connections barely existed. The “Evangelion” movie was not out in America — no official release. I needed to see it. I found a tape-trading website. You mail in a tape, or pay for shipping and a blank tape, and you get back your fansubbed anime of choice. I got into it because it was a cheap way to get all kinds of stuff that was totally unavailable in any official capacity. I could send fifteen dollars to my connection and get three tapes back filled with features or episodes.

All of this is before DVD enters the picture.

GC: Thank goodness for Comic Junction.

TJ: When I told Kip at Comic Junction that I had gotten into the fansub thing, we made a few trades.

GC: I never got into anime the way you did, but Kip recommended some great titles to me.

TJ: It was like going to a great record store and discovering something new thanks to the knowledge of the person behind the counter. The first time I went to Comic Junction was because I had heard about “Evangelion.” When I got there, the tape was checked out. Kip said, “I’m sorry that one is not in, but let me suggest another cool show you might like.” It was “Patlabor,” which was awesome.

GC: When the DVD explosion happened, did you feel compelled to re-purchase certain things?

TJ: You make choices based on your budget. Do you double-dip or buy something new? At that time in my life it was all about collecting something new. “Evangelion” stayed on the shelf as tapes so I could add “Cowboy Bebop” on DVD.

I was an anime fan before I was a cinephile. But one led directly to the other.

GC: What was the movie that opened things up?

TJ: Everyone has that movie that blows their mind. I rented “Fight Club” one weekend. I didn’t know anything about it. And then my sister told me to add “The Virgin Suicides” at the same time. So I saw both those movies back-to-back. And they hit the same part of my brain the way anime had before. I realized that the feeling of connecting to art and how art could expand my understanding of life and learning and appreciating did not belong exclusively to the realm of anime.

From that point on, anyone I knew who was into movies became a source of information.

GC: But even when you were really young, you had a deep interest in how to tell stories visually. You made movies long before you ever saw “Fight Club” and “The Virgin Suicides.”

TJ: Yes, for sure. I started making comics in first grade. And my dad brought a VHS camcorder home from his office. I became obsessed with trying to shoot stuff all the time. When friends came over, I insisted we make a movie or draw some comics.

But at that time, I had no understanding of formal technique. I just went on instinct and a desire to create. Just the pleasure of doing it.

GC: Were there any household rules or restrictions about what you were allowed to consume?

TJ: There was an attempt to keep an eye on me, but the climate was pretty lax pretty early. It got to the point where Cash Wise would have me call my mom to get permission when I wanted to rent a movie. I crossed the Rubicon with “A Clockwork Orange.” My mom finally told the video store to let me rent whatever I wanted and not to bother calling her anymore. I was probably fifteen when the restrictions went away.

GC: I begged my mom to let me see “Psycho” when it was playing on television. She warned me that it would give me nightmares but reluctantly agreed to let me watch. I did have nightmares, but I was also ecstatic.

TJ: I experienced feelings of shame and discomfort even after I had the green light to watch grown-up movies. I thought, “I may be allowed, but I still don’t want you to know what I’m watching.”

GC: My grandmother watched “The Breakfast Club” with me once. I had to leave the room frequently to get drinks of water.

TJ: I was at my friend Cody’s house and his parents invited us to watch “Me, Myself & Irene” with them.

GC: How are you curating your collection today?

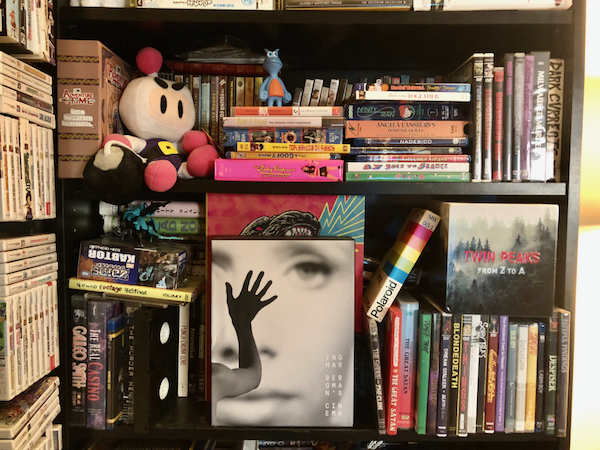

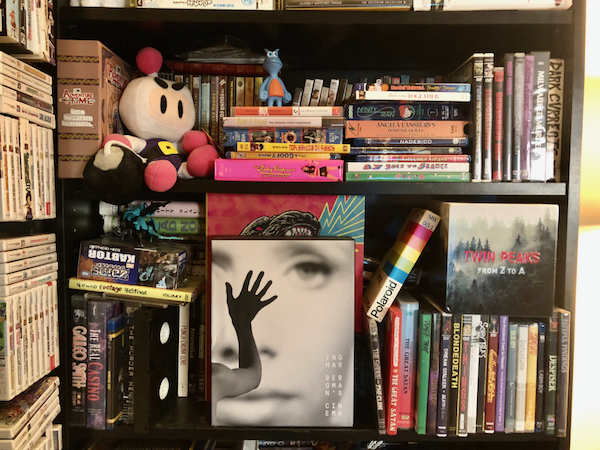

TJ: It’s a hodgepodge. It represents many phases and many eras. What’s on the shelves now is a Frankenstein’s monster of layers upon layers. It’s hard for me to organize after moving several times. The discs-by-mail version of Netflix coincided with me going to college. I could go to the college library or the local arthouse and of course rent Criterion Collection movies from Netflix.

Talk about eating your vegetables. Every single day I was dining on the world’s biggest salad bowl. It was like mainlining film history. I would ask for Criterion movies for my birthday. I still get excited about stuff like the big Ingmar Bergman set. But recently I have acquired more amateur and outsider filmmaking.

GC: I wouldn’t even know about Paul Knop if not for you.

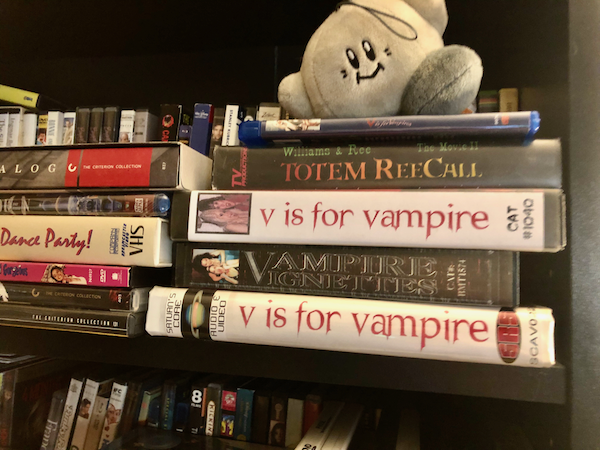

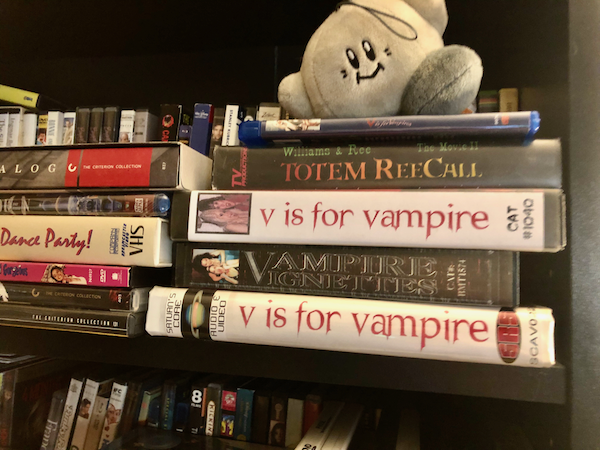

TJ: Some things that I like are obscure enough that a digital file isn’t an option. I got turned on to Paul Knop at a Found Crap screening in Los Angeles where Rob Schrab and Dan Harmon would play stuff from their collections. Clips of bizarre, midwestern, VHS, homemade vampire movies. I immediately connected.

It reminded me of certain 2-Minute Movie Contest entries or 48 Hour Film Project movies. The kind of locally-produced creative work and amateur art that was only shared in a very small circle. You relate because you see yourself in them. I appreciate someone who gets a bunch of friends together on a weekend to film something. I have so much respect for people who, regardless of their means, make it happen.

GC: In every town there is someone like Paul Knop pursuing the dream.

TJ: His movies were shot and released on video mostly in the 90s. Small print runs. How do I access these movies? You couldn’t find them. I searched for several years. When one popped up one day on eBay, I got outbid. That lit a fire under me. Facebook tape trading groups were a place for people to share their collections of the rarest and most obscure titles. I would comb through these groups.

I eventually found a sub-group of a sub-group of people into vampire movies. Somebody had original Paul Knop tapes but did not want to sell. I was so desperate, I bought a dual VHS dubbing deck and had the machine mailed to this man’s house so he could make a copy of “Vampire Vignettes” for me.

GC: That is commitment.

TJ: There’s nothing more exciting than an amateur film or a student film.

GC: How do you organize your movies?

TJ: As a kid, you have this dream that you will one day do everything possible to showcase your beautiful collection. But the reality for me is partly a personal thing, partly a practical thing. My shelves are full, so when I get a new item, it usually gets randomly plopped down wherever it might fit. Piles on top of piles.