Interview by Greg Carlson

My friend Mike Scholtz, the director of “Riplist” and many other fantastic documentaries, collects movies when he’s not making them. He especially likes VHS and once rescued the children of Pine City, Minnesota by purchasing tapes of “Fritz the Cat” and “Flesh Gordon” that had been shelved in the local thrift store’s kid video section.

GC: Are you format agnostic?

MS: It never bothers me when I watch a movie on VHS, even if I know I could be watching it on 4K. It doesn’t even register with me. I’m sort of the opposite of a snob when it comes to resolution or the latest technology.

GC: I like 4K, but when VHS offers content that you can’t get anywhere else, that’s a good argument for the format.

MS: There’s also a pleasure in watching a film on VHS that you vividly remember watching on that format originally. Like back when you were a kid.

GC: Like Paolo Cherchi Usai suggests in his book “Burning Passions,” the viewing context shapes and informs our understanding and perception of each movie we experience. What are you watching?

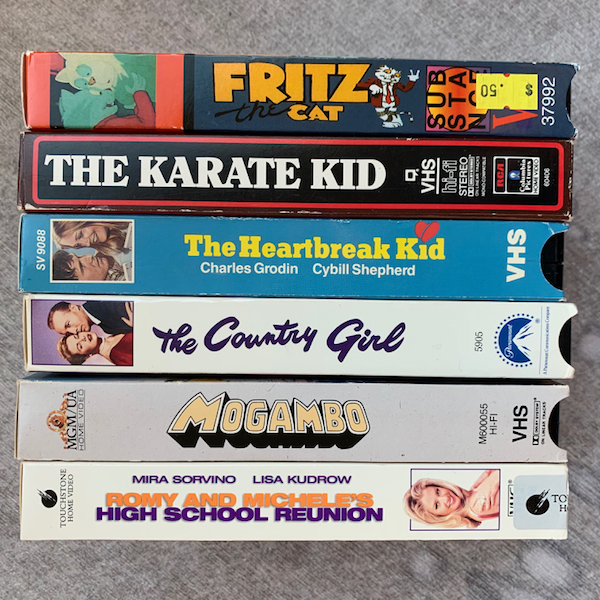

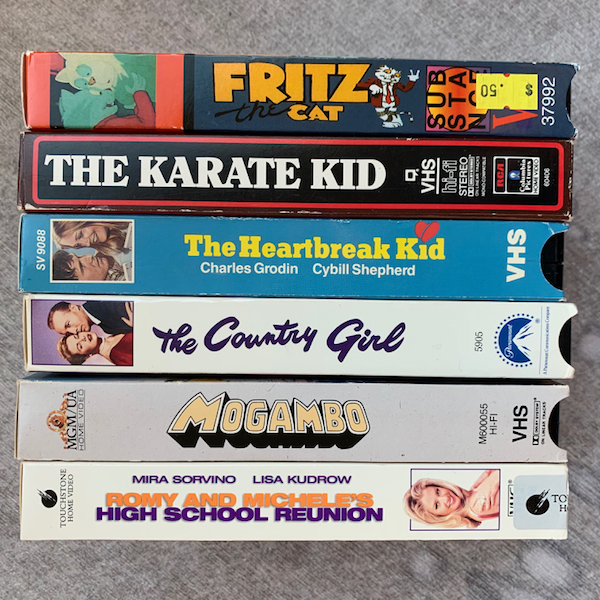

MS: I started “The Karate Kid” last night, on VHS, which is where I originally saw it.

GC: I almost can’t believe you never saw “The Karate Kid” theatrically.

MS: The first time I saw it was on VHS. I don’t think I’ve ever watched it any other way than VHS. I cannot even imagine what I’m missing. I’m probably missing something. I didn’t finish watching it yet, but I’ve been enjoying it. Such a great hangout movie. I love hanging out with Daniel and Miyagi just clipping bonsai trees. It’s so fun. No modern film would spend as much time just clipping bonsai trees, as that movie does.

GC: “The Karate Kid” is one of my favorite movies. I’m doing a deep dive this year on the films of 1984.

MS: Have you rewatched it recently?

GC: I showed the recent 4K to my 12-year-old son. He enjoyed it. I saw “The Karate Kid” in the theatre two or three times in 1984, and then my grandpa made me a VHS copy. I brought the tape over to my friend Jim’s house, and in those days, different decks had all kinds of curious features. Jim’s family VCR had an audio dub button. We accidentally bumped it during the scene when Daniel is practicing his balance in Miyagi’s boat. And now there is about a five or ten second sound clip on my VHS tape of some golf commentators talking under those images.

MS: When I taped “North by Northwest” from Prairie Public Television sometime in the 1980s, the audio dropped out during the auction scene. So on the VHS copy that I had for years and years, the only copy I watched, the entire auction scene plays silent. “North by Northwest” probably played at the Fargo Theatre at some point in the 1980s, so I have seen the scene, obviously, but I sort of prefer the first way I saw it — with a silent auction. Hitchcock is so good, you know what is happening. You almost don’t miss the audio. I love when things like that happen.

GC: Do you keep track of how many movies you have in your collection?

MS: We had to start keeping track of the VHS tapes, because I was accidentally double-buying too often. You go to a thrift store and you see stuff … I have too many tapes to remember everything I have. I have more than 1300 VHS tapes and I keep a database I can check on my phone. I don’t always remember which Julia Roberts romantic comedies I have, other than “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” which is one of the best movies ever made. I couldn’t remember if I had “Pretty Woman” and “The Runaway Bride,” so it would get fuzzy in my brain.

GC: Do you keep formats other than VHS?

MS: I do have stuff on all the formats. I have not gotten into 4K yet but I have more than 100 LaserDiscs, maybe 800 DVDs, probably 300 Blu-rays. I have a couple Betamax tapes that friends have given to me, finding interesting things out in the wild. I have a few old CEDs that sort of look like LaserDiscs, but aren’t. My friend Annie keeps buying those for me. I have the disc of “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas,” which I cherish.

GC: Do you re-purchase titles across formats?

MS: There are a few movies I collect in multiple formats. I don’t know why I’m driven to do that for certain movies, since they are not even necessarily my favorite movies. I do have “Ishtar” in every format ever released. And that is one of my favorites.

On the other hand, I don’t really like the James Bond movie “Die Another Day” but I think I just like the artwork, so I’ve almost accidentally collected that movie in multiple formats.

The only other films I purchase every time I see them are “The Heartbreak Kid” and “Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.”

GC: What is your favorite genre to collect?

MS: I’m most delighted by late 1960s and early 1970s science fiction, like “Silent Running,” “Logan’s Run,” Godzilla movies, the “Planet of the Apes” series. I love finding those out in the wild. I own three copies of “Escape from the Planet of the Apes.” I just can’t seem to help myself.

GC: Do you have a single favorite item in your collection?

MS: My VHS of “The Heartbreak Kid” is one because it’s an Elaine May film and she’s one of my favorite directors. It was hard to find, and still isn’t easy to find, on DVD. There’s an out-of-print Anchor Bay disc that was released in 2002. So I like the feeling of exclusivity. I shouldn’t care that it’s rarer, but it does feel special.

GC: Rarity and scarcity are things that drive so many collectors. If you know you can’t get something, you want it more. Do you look for specific titles or blind-buy?

MS: I have spent more time lately online and on eBay searching for specific titles that I want on VHS. I just bought “The Country Girl.” It was the one remaining Grace Kelly film that I had not seen. It’s not a rare film, but it was harder for me to acquire on VHS. I ordered a copy that was lost in transit, so I went back to eBay to try again, and finally got it in the mail yesterday.

I may become interested in an actor or a director because I stop at a library sale or thrift store and see a huge run of someone’s films. I went to a sale in Hayward, Wisconsin and found ten Gary Cooper films on VHS. I just bought them. I love “High Noon” and I like Gary Cooper, but I probably wouldn’t have engaged in a Cooper viewing project if I hadn’t run across those tapes.

I really like the universe randomly dictating what I’m going to be interested in next. But I do balance chance discovery with searching for specific things.

GC: One of the great home video collecting tragedies is the replacement of original soundtrack music when licensing is prohibitively expensive. It is annoying and horrible. I just rewatched “The Wild Life,” which is such a time capsule of 1984, and in the original release, there are key scenes scored with Prince, Madonna, and Billy Idol. None of those three big needle-drops made it to the Universal Vault Series on-demand disc, and it just ruins the viewing experience.

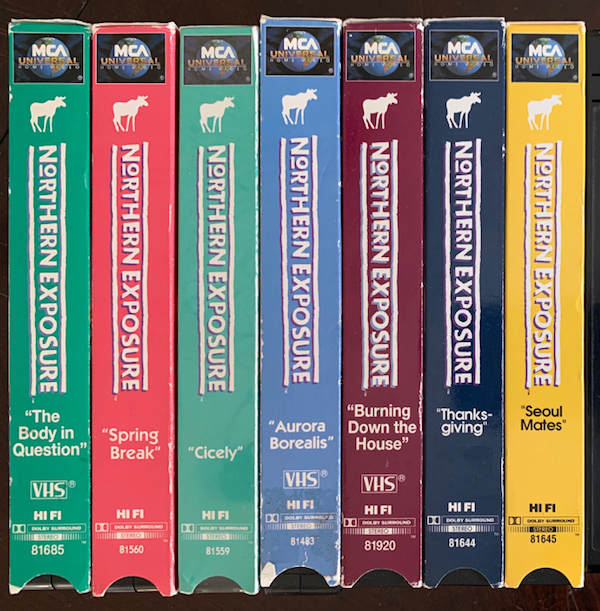

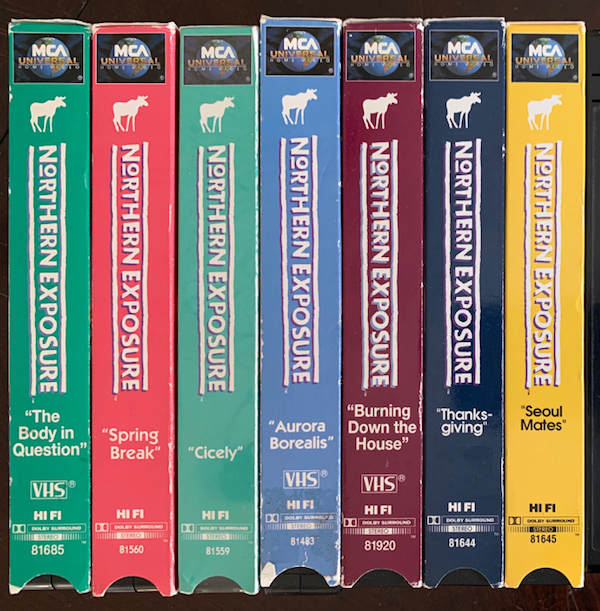

MS: The “Northern Exposure” DVD sets replace those great songs from the broadcasts, but for some reason the 11 VHS tapes retain the original music choices, which were so important to the atmosphere of the show. So VHS is a better way to watch those episodes.

The Rankin/Bass VHS tape of “The Hobbit” has a unique sound effects track that some fans seek out.

Another example is “Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster.” The 1972 American release had different opening title music, with an English-language version of the song called “Save the Earth.” It’s a great anti-pollution, pro-Earth song, and it’s only available on VHS. Not even the massive new Criterion release has it. I was hoping that set would have included it as an alternate track.

GC: How do you organize your collection?

MS: We had the entire collection in our spare bedrooms for a long time, and it was completely disorganized. The movies were just crammed into shelves, and there were just too many tapes. I finally have them alphabetized, but now they are in giant plastic bins out in a shed that we call our warehouse. I rotate titles in and out all the time.

I would love to have a video store setup, but we don’t have the space.

GC: Setting up a video store is the fantasy of so many collectors, whether you would actually rent out the tapes or not. Just having a place to hang out and talk about movies all day.

MS: My friend Joe set up a VHS horror shop in his basement. He called me up and asked for as many VHS horror movies as I could spare. So I did get to go to his basement video store and stock the shelves. It was a dream come true.

+++

Mike’s movie “Riplist” is not currently available on VHS, but you can stream it for six bucks from the Twin Cities Film Festival.