Preview by Greg Carlson

The 19th Fargo Film Festival begins on Tuesday, March 19th and runs until Saturday, March 23. Continuing a tradition of quality local arts programming, the event provides both casual moviegoers and cinephiles with multiple opportunities to see remarkable shorts and features on the two big screens of the Fargo Theatre. Guided by Fargo Theatre Executive Director Emily Beck, organizers work year-round to prepare for the largest annual moving image event in the state of North Dakota.

Many of the movies screened at the Fargo Film Festival are supported in person by the professionals who made them, and the festival has developed a reputation over the past eighteen years as a warm and welcoming place for filmmakers to share their hard work with enthusiastic viewers in a stunning setting equipped with state-of-the-art projection and sound. The accessibility of the visiting guests delights audience members and festival volunteers alike.

Narrative short jury chair Michael Stromenger echoes the feelings of many when he says, “The Fargo Film Festival gives us the opportunity to celebrate film and share our love of it with a wonderful community of filmmakers, festival-goers, and volunteers. I look forward every year to discovering new films, meeting talented filmmakers, and making a whole new set of treasured memories.”

Narrative feature jury chair Tom Speer concurs, saying, “There’s a difference between seeing a film and having an experience. That’s what makes the Fargo Film Festival so special. Whenever I meet someone who’s never been to the FFF, I tell them, ‘This is your festival.’ We really do have something for everyone here.”

Evening Showcases

FFF19 boasts one of the festival’s all-time strongest line-ups, and the evening showcases, while a great place to start for newcomers, might just serve as a gateway to more sessions and discoveries.

On Tuesday, March 19, the festival’s opening night film is “Bathtubs Over Broadway,” a feature documentary examining one man’s fascination with long-lost and barely-remembered industrial musicals preserved on souvenir, “not for broadcast” LPs. Director Dava Whisenant will attend the festival with subject Steve Young, the longtime “Late Show with David Letterman” writer whose obsession has brought some much deserved attention to the likes of American-Standard’s “The Bathrooms Are Coming!” and many more too-good-to-be-true productions.

Fargo-Moorhead native, Fargo Film Festival veteran and 2018 Ted M. Larson Award recipient Mike Scholtz unveils the world premiere of his latest project on Wednesday, March 20 at 7:00 p.m. Beck says, “I can’t wait to share the new documentary ‘Riplist’ with Fargo audiences. The film follows a group of friends who participate in a celebrity deadpool, a delightfully morbid hobby in the vein of fantasy football… except you draft famous people you think might die in the next year. It is wickedly funny, insightful, and fascinating — the exact sort of excellence we’ve come to expect from Minnesota filmmaker Mike Scholtz.”

Thursday, March 21 is reserved for fans of sweet jumps, tater tots, and time machines, as a partnership between Jade Presents and the Fargo Film Festival welcomes “Napoleon Dynamite” stars Jon Heder and Efren Ramirez to the stage of the Fargo Theatre for an entertaining conversation about the modern cult classic now celebrating its fifteenth anniversary. The Q and A will be preceded by a screening of “Napoleon Dynamite” in its entirety, so don’t forget your Caboodles.

Legendary visual effects pioneer, industry giant and four-time Oscar winner Richard Edlund will receive the Ted M. Larson Award, the highest honor bestowed by the Fargo Film Festival, on Friday, March 22. At 7:00 p.m., Edlund will reflect on his still-unfolding career. Beck says, “His work on ‘Star Wars,’ ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’ ‘Ghostbusters,’ and countless other iconic films helped shape my love of cinema. It will be nothing short of an honor to have him on the Fargo Theatre stage. I get goosebumps just thinking about it.”

The regional premiere on Saturday afternoon of Martha Stephens’s “To the Stars,” produced by locals Jeff Schlossman, Karen Schlossman, Bill Wallwork, and Erik Rommesmo of Northern Lights Films, offers filmgoers a rare, early look at a movie that debuted a few weeks ago at the Sundance Film Festival. A beautifully realized coming-of-age story following two teenagers in 1960s Oklahoma, “To the Stars” is anchored by strong performances from leads Kara Hayward (“Moonrise Kingdom”) and Liana Liberato (“Trust”), as well as memorable assists by veterans Malin Akerman, Tony Hale, and Shea Whigham. Filmmakers will participate in a Q and A following the movie.

The closing night “Best of the Fest” session starting at 7:00 p.m. on March 23 begins with the presentation of the Margie Bailly Volunteer Spirit Award to Kari Arntson and a screening of the winner of Friday night’s annual 2-Minute Movie Contest. Viewers will then see a trio of powerful shorts. Animation chair Sean Volk says, “Randall Christopher’s “The Driver Is Red,” winner of our Best Animated Film, is an exhilarating example of documentary filmmaking with the pace and urgency of a thriller. In the film, a secret agent hunts an exiled Nazi in Argentina; it’s an impressive work that challenges conventions of what people think about when they consider animation.”

Cy Dodson’s “Beneath the Ink,” which visits a tattoo artist devoted to covering up symbols of hate, will precede Celine Held and Logan George’s “Caroline,” a harrowing exercise in perspective-taking. Both Christopher and Dodson will attend the festival.

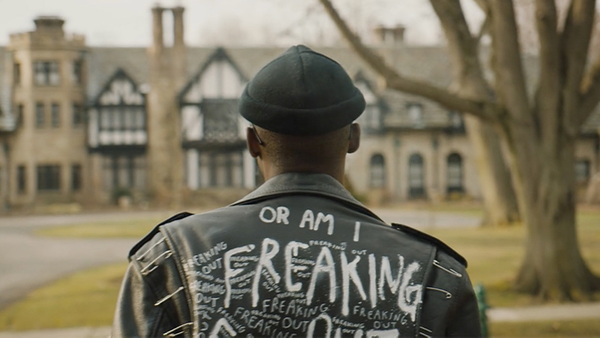

Saturday evening concludes with a special screening of Nia DaCosta’s tense and poignant “Little Woods.” Speer says, “I’m excited for this film for several reasons. ‘Little Woods’ was selected to receive our Best Narrative Feature honor, and the North Dakota setting should appeal to a lot of curious viewers. The movie stars Tessa Thompson, whose stock is absolutely soaring into the stratosphere right now. Her subtle yet potent performance will not be easily forgotten.”

Animation

Volk brings his previous experience from the Nashville Film Festival to Fargo as jury chair of the animation category.

Volk says, “The animation category is packed with incredible talent this year. The category showcases a variety of styles and techniques all while presenting deeply personal and human stories. An honorable mention recipient, ‘Weekends,’ directed by Trevor Jimenez, was just nominated for an Oscar and it is easy to see why: Jimenez creates something strikingly intimate and purely visual as he recounts the story of a young boy navigating the realities of his parents’ divorce.”

Volk goes on to highlight one of his personal favorites in the category, “Carlotta’s Face.” Directed by Valentin Riedl and Frederic Schulz, the film is about a woman who uses art to process the world around her as she struggles with a condition that leaves her unable to recognize faces. Volk says, “It’s beautiful and it made me cry so hard. After I finished it the first time, I had to go back and watch it twice more so that I could live in its emotion and energy a little longer.”

Documentary Short

Along with highly relevant category winner “Beneath the Ink,” documentary short chair and Margie Bailly Volunteer Spirit Award recipient Kari Arntson recommends several of the documentary short subjects, including “Bernie Langille Wants to Know… Who Killed Bernie Langille” for its unique approach to storytelling. The film, which premiered at Hot Docs, uses detailed miniatures to explore the mysterious 1968 death of a military electrician.

Documentary Feature

Documentary Feature jury chair Kendra O’Brien is proud of category winner and opening night movie “Bathtubs Over Broadway.” She says, “The film is a delight. It’s beautifully shot and edited and will have you singing to your friends about diesel engines and bathroom fixtures. Every year I’m amazed at the new communities I’m introduced to, and this one is a gem.”

O’Brien also encourages viewers to see festival veteran Melody Gilbert’s “Silicone Soul.” She notes, “Melody’s movie is a caring, human, and silicone portrait of a fringe community. I want to meet people for coffee or drinks after to discuss.”

Narrative Short

Stromenger says he can’t wait for audiences to experience “Caroline” and “Fauve,” noting, “These are two beautifully crafted films about young kids making tough choices in difficult situations and they both pack an emotional wallop that stays with you long after they’re over. They’re the cream of the crop in one of the most competitive years we’ve had in this category.” “Fauve” was recently nominated for an Oscar.

Narrative Feature

Speer says he is “very excited for everyone to see the fascinating indie sci-fi film ‘Prospect,’” noting that filmmakers Christopher Caldwell and Zeek Earl “create the setting using practical effects and camera and editing techniques. The result is nothing short of breathtaking.” Speer also praises the film’s ensemble, including remarkable newcomer Sophie Thatcher, indie film icon Jay Duplass, and “Game of Thrones” alum Pedro Pascal, who was recently cast as the lead in “The Mandalorian,” Disney’s first live action “Star Wars” series.

Films, Filmmakers, and More

In addition to the categories highlighted above, the Fargo Film Festival also offers incisive lunch panels, the annual Thursday night party at Moorhead’s All-Star Bowl, and the popular 2-Minute Movie Contest. The festival also continues to support and program sharp and thought-provoking movies in experimental and student filmmaking. With dozens of titles from which to choose, viewers can expect to fall in love with stories they may not have an opportunity to see anywhere else.

A PDF of the complete glossy program is available at fargofilmfestival.org and tickets are on sale now at the Fargo Theatre box office.