Review by Greg Carlson

WARNING: The following review reveals information and details contained within the live show. Read only if you have seen “The Empire Strips Back.”

Embarking on an inaugural tour of Canada and a return to the United States following a 2018 run, Australian burlesque impresario and creative director Russall S. Beattie’s “The Empire Strips Back” invites audiences to celebrate a vision of Star Wars fandom typically hidden from the carefully curated, family-friendly brand now overseen by Disney. An adults-only show currently featuring a cast of ten performers (seven women and three men), the wildly imaginative and vividly staged revue emphasizes heterosexual male fantasy while making room for at least some amount of queered content.

Milwaukee’s historic Pabst Theater, the closest venue to Fargo on the current tour, hosted “The Empire Strips Back” on Saturday, April 13. With enthusiastic voice, a nearly full house greeted the high and low witticisms of Drew Fairley’s master of ceremonies. Fairley, who mainly works the crowd with front-of-drape banter during set and costume changes, plays a properly British-accented, rebellion-hating Imperial officer in the first section and returns after intermission as Dook Skywalker, a Tatooine-by-way-of-Sydney X-wing pilot with a generous wig. He also croons Michael Jackson’s “Ben” to an impressive holographic projection and blasts through some reworked bars of “Rapper’s Delight.”

The affable hype man steers clear each time the curtain rises on a beautifully-lit spectacle. Like so much great theatrical presentation, “The Empire Strips Back” does a lot with a little. Individual physical components, including multiple background creatures and a fully functional R2-D2, tauntaun, and Jabba the Hutt, cultivate an air of verisimilitude that expertly threads the needle between polished professionalism and a kind of handmade, DIY aesthetic that suggests scrappy, entrepreneurial kids putting on a summertime play in the backyard. The focus of the viewer is subsequently pointed with force — pun intended — on the lithe ecdysiasts.

Despite offering less body-type variation than one might usually see in contemporary American-style striptease/burlesque shows, one of the most satisfying curiosities of “The Empire Strips Back” can be found in the liberal gender swapping of male and traditionally masculine characters. While no boys inhabit any version of Leia or the other scarce women of the original trilogy, the show features a squad of female stormtroopers and female embodiments of Luke, Vader, C-3PO, Boba Fett, and a few others. Veteran dancer Kael Murray, who plays both the heroic farmboy and the golden protocol droid (as well as a stormtrooper), is undoubtedly one of the production’s MVPs and has spoken earnestly to the importance of staying true to Skywalker’s youth and optimism in her interpretation.

Her landspeeder soapdown set to Nicki Minaj’s “Starships” is one of many highlights. Personal tastes vary, but Beattie’s crafty song choices, which range from obvious to sublime, buoy numbers like the trio of crimson-clad Royal Guards (as elite here as their screen counterparts are next to the throne) moving to Die Antwoord’s “Baby’s on Fire.” Moody and seductive, the sapphic pas de deux of Twi’leks lamenting their fate to Portishead’s hypnotic “Roads” is equally enthralling. Run-DMC’s “It’s Tricky” sets the thematic tone in a wild boombox medley exploring the unbreakable fraternal bond of Han and Chewie’s very special interspecies relationship.

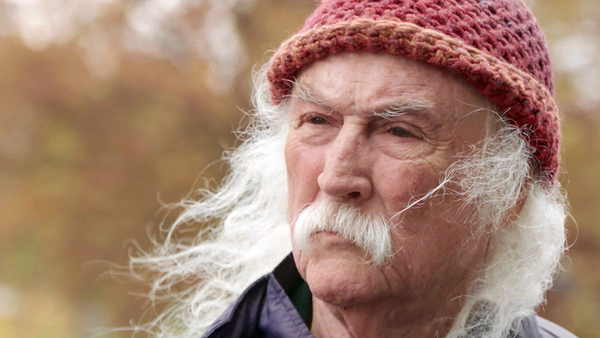

Because it was barely more than 24 hours since J. J. Abrams and Kathleen Kennedy had shared the Palpatine bombshell teaser for “The Rise of Skywalker” in Chicago, the outrageous appearance of the Emperor took on a heightened position of prominence in Milwaukee. Far and away the evening’s most ribald provocation, the sequence opens with the chalky, wrinkly epidermis of the one-time chancellor playing peekaboo from behind the heavy black robe and cowl. No mere phantom menace this time, the galaxy’s greatest puppetmaster peels off to Q Lazzarus’ “Goodbye Horses” in a tucked and untucked homage to Buffalo Bill’s famous posing in “The Silence of the Lambs.”

In “Using the Force: Creativity, Community and ‘Star Wars’ Fans,” Will Brooker remarks that true believers and flamekeepers are often “custodians of their chosen text, rehabilitating and sustaining the characters through their own creations.” “The Empire Strips Back” is a reminder that intellectual ownership is an elastic concept once something has so thoroughly permeated the popular culture. Fortunately, copyright law protects parody — although one imagines Beattie’s legal team is still handsomely compensated to stay outside Lucasfilm/Disney’s crosshairs.

A long time ago, during the making of the original “Star Wars,” George Lucas famously downplayed any eroticism by insisting that Carrie Fisher’s torso be stabilized with gaffer’s tape. Quoted in Peter Biskind’s “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls,” Fisher corroborated, saying, “No breasts bouncing in space, there’s no jiggling in the Empire.” A couple years and a few million dollars later, the filmmaker would greenlight Fisher strapping on the soon-to-be iconic slave girl bikini. So even within the galaxy Lucas built, it’s complicated. Asher Bowen-Saunders, by the way, makes an absolutely smashing Princess Leia in and out of costume in “The Empire Strips Back.”

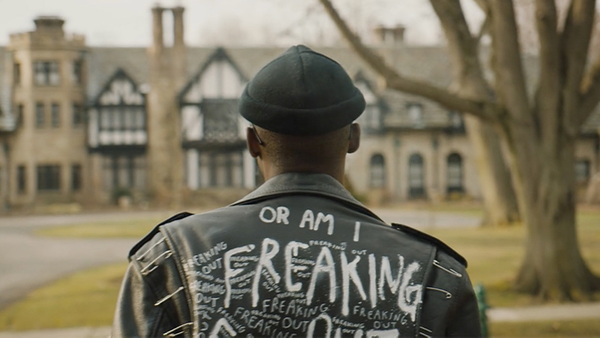

What might the future of sexuality hold in the Star Wars universe? The sanctioned material of the current series, outside of Finn’s apparent omnisexual appeal or whatever chemical reaction a fleeting glimpse of Kylo Ren’s bare chest might stir in Rey, will surely remain committed to the chaste nonsense of Jedi vows of celibacy and the soap opera’s infatuation with matters of paternity. It shall be up to the freaks, the perverts, the anarchists, the fanfic authors, the cosplayers, the kit-bashers, and the customizers to keep expanding, inventing, imagining, and remixing the unknown pleasures beyond the Outer Rim.