Movie review by Greg Carlson

An occasionally stimulating, often perplexing treatment of the nature of guilt, redemption, and the responsibility taken (or not taken) for one’s actions, “The Reader” is the kind of film designed to entice award season kingmakers. Two of the film’s producers – Anthony Minghella and Sydney Pollack – died prior to the movie’s release, and the fact that both men are Academy Award winners adds a measure of luster and sentimentality to the film’s pedigree. Directed by Stephen Daldry from the novel by Bernhard Schlink, “The Reader” does not risk enough to distinguish it from some of last year’s other handsomely photographed period films.

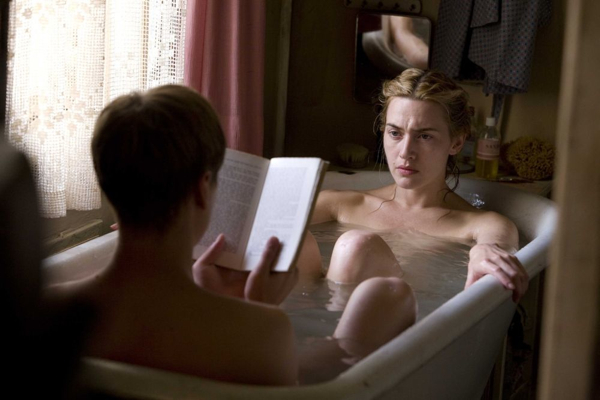

Tinkering just a bit with the chronology but otherwise sticking close to the events described in Schlink’s text (available in an English translation by Carol Brown Janeway), Daldry’s film initially traces the sexual awakening of 15-year-old Michael Berg (David Kross), a schoolboy in post-World War II Germany who shares a brief but intense affair with a woman more than twice his age. Kate Winslet, as Berg’s lover Hanna Schmitz, brings much more to the role than is offered by David Hare’s script, which never attempts, or dares, to peer inside the mind of a person intimately acquainted with the unthinkable power of decision-making over life and death.

It is no spoiler to reveal that Hanna was a concentration camp guard who served in the S.S., although Daldry plays the scene in which this information is revealed as one of the movie’s two essential surprises. The challenge for someone attempting a critical assessment of the story is to account for Berg’s curious relationship with Hanna after he discovers her complicity in the horrors perpetrated under the reign of the Third Reich. While a second examination of the title suggests more than one possible assignation, the movie’s point of view belongs decidedly to Berg, even though Hanna dominates his thoughts from the first frame to the last.

Following the publication of Schlink’s novel in 1995 (the translation debuted in 1997), some controversy was inspired by the sympathetic portrayal of Hanna. Many of the arguments, however, missed the essence of the author’s questions related to the generations of Germans coming of age after the end of the Nazis: is everyone responsible? Hanna often asks those who stand in judgment of her “What would you have done?” and the query can have a chilling effect. Neither Schlink nor the filmmakers explicitly forgive Hanna for “merely” following orders, but there is no doubt that viewers are meant to sympathize with her.

While Berg is portrayed by both Kross and Ralph Fiennes to represent the character at different points in his life, Winslet attempts to handle the younger and older versions of Hanna. The movie’s first major section, effectively and often erotically detailing the heavily heterosexual male fantasy of Berg’s carnal education, is the film’s strongest, as Kross and Winslet seem to spend as much time in the bed or bathtub as they do with their clothes on. Winslet does not fare as well buried under old-age makeup, but the overall impact of her performance is on par with her strongest work to date.