Movie review by Greg Carlson

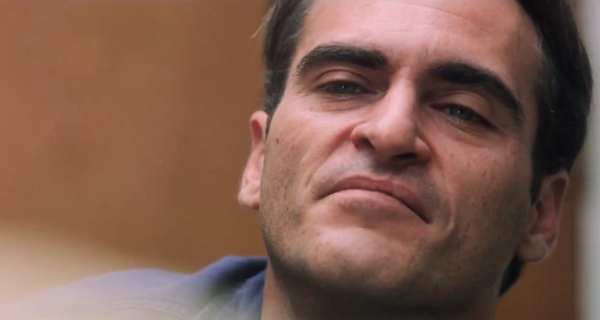

It goes without saying that many film students and wannabe auteurs will worship at the feet of “The Master,” another audacious, dazzling, and occasionally frustrating tour de force from the preternaturally gifted Paul Thomas Anderson. Highly anticipated as a potential expose itching to pull back the curtain on Scientology, the film functions instead as a rich character study of two particular types of American loser. The first is Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), a misguided sailor in the U.S. Navy marking time in the South Pacific during the waning days of World War II. A deliberately unlikable alcoholic quick to outbursts of violence, Freddie is a self-taught mixologist, experimenting with paint thinner, photo processing chemicals, and any other available toxic substance that might give him a buzz.

Lost, angry, and very likely seriously mentally ill, Freddie blacks out and wakes up on a yacht commanded by Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a self-confident conman of the highest order who introduces himself by saying to Quell, “I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher, but above all, I am a man, just like you.” Dodd is enough like Charles Foster Kane that one would not have been surprised to hear him add newspaper publisher to the list of his achievements. To the chagrin of his family and inner-circle, Dodd falls hard for Freddie, inviting him to join the traveling circus Dodd calls “The Cause,” a cult-like system that blends fantasy, science, and sense memory with the power of suggestion in intense, therapeutic “processing” sessions, sometimes conducted one-on-one and sometimes played out in front of a roomful of spectators.

“The Master” most closely resembles Anderson’s own “There Will Be Blood,” both as portrait of outsize dreamers and as clinic on male screen performance. Amy Adams, as Dodd’s wife Peggy, is allowed but a fraction of the screen time devoted to the movie’s real romance between Freddie and Lancaster. If only PTA loved women as much as he loved men, Adams might have been given more moments like the fantastic scene in which she brings her husband to climax over a bathroom sink. Truly private, it is one of the few times in the film Anderson allows a glimpse of the Master without his shield, and suggests at least the possibility that the hand that rocks more than the cradle rules Dodd’s world.

“The Master” is by turns claustrophobic and panoramic, although the former outpaces the latter in scene after scene of intimate medium and close shots in which many speeches are given and “applications” are administered. The highly presentational nature of Dodd’s movement/religion incorporates and even demands that the Master’s every word be documented, a strategy that affords Anderson the luxury of non-stop grandstanding every time Lancaster opens his mouth – which is a great deal more than Freddie, who is often photographed in reaction, gazing at his mentor in wide-eyed awe.

The best moments in “The Master,” including the much-discussed barking mad jail scene, indicate that underneath his collected, controlled exterior Dodd is every bit as unhinged and fragile as Freddie. Jealous of Freddie’s unselfconsciousness, Dodd manipulates and abuses his friend, who masochistically takes everything dished out to him and comes back for more. By the time the Master croons the second of his two major musical performances, we may not understand much, but we will have seen that Lancaster contains within himself a riot only Quell can quell.