Movie review by Greg Carlson

A largely disappointing follow-up to his wild dissection of the methodology of Stanley Kubrick in “Room 237,” Rodney Ascher’s “The Nightmare” introduces an octet of bedeviled souls afflicted by sleep paralysis. Staging chilling reenactments that unfold like the lurid spine-tinglers on television’s “Unsolved Mysteries,” Ascher enjoys his role as deliberately neutral interlocutor, leaving it to the viewer to decide whether the filmmaker sees his subjects as worthy of genuine pity or eye-rolling derision. By the time we reach the end, the concept runs on fumes, frustrating anyone hoping for reasonable scientific verification of the awful and eerily similar experiences described.

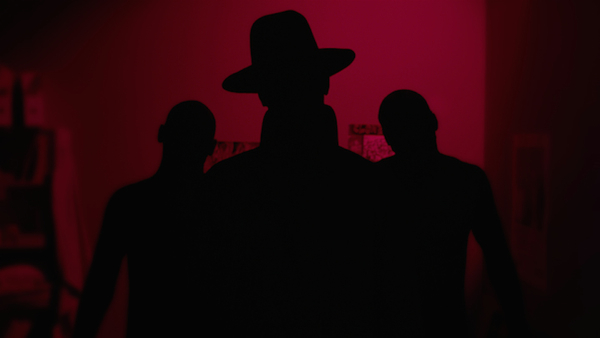

Whether one is a lucid dreamer or dead-to-the-world slumberer, the particulars of sleep paralysis sound downright hair-raising: essentially trapped in a state of consciousness, victims find themselves completely unable to move so much as a muscle while buzzing electrical currents course through the nervous system and shadowy figures creep into view. Those unwelcome visitors, usually men and sometimes in hats, bear down on their petrified prey. Some have eyes that glow bright red. Occasionally, cats or catlike creatures akin to the incubus of Henry Fuseli’s iconic and best-known painting come calling. One poor guy is regularly attended by grinning aliens made of static.

But where is Robert Stack when you need him? Once Ascher finishes cross-cutting among the individual variations, one expects the film to shift into some kind of deeper or more careful consideration of these waking dreams. Instead, he eschews medical explanations, sleep physicians and researchers, tossing out pretty much any contextualizing counterpoint to the woeful tales of the damned. Some of the subjects hint at personal trauma that deserves some additional acknowledgment. Many viewers will simply dismiss the visions as byproducts of stress that emerge as manifestations of how a body might psychologically deal with emotional drain, threat, or demand.

Deep into the movie, Ascher nearly escapes the hole he has dug. Using clips from several films, including “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” “Communion,” and even “Natural Born Killers” the filmmaker sets up what appears to be an attempt to link the horrifying apparitions visited upon his interview subjects with similar motifs in popular culture. Unfortunately, the kooky, energetic approach to film clip illustrations that worked so well in “Room 237” stops before it can make an impact. Ascher refrains from exploring the obvious question: do those dealing with sleep paralysis construct their demons from the potent images created by storytellers, or are these archetypes made of something more primal?

Ascher’s strategy to conjure up the willies for his audience results in more fantods than frights. How come we never get to know any of the sufferers as fully functioning human beings with jobs and family members? Beyond the briefest mentions of non-nightmare mundanities, the director limits the content of the talking heads to detailed explications of the physically and mentally exhausting dread awaiting the unlucky when they could use a good night’s rest. Ghost stories around the campfire have always fueled our imagination, but skeptics will become impatient with “The Nightmare” long before it is time to wake up.