Movie review by Greg Carlson

Mark Hartley’s “Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films” sprays viewers with an Uzi-like barrage of film clips, trailers, promo reels, and talking heads to spin the tale of 1980s powerhouse schlock heavyweights – and cousins – Manahem Golan and Yoram Globus. A competitor and companion to Hila Medalia’s “The Go-Go Boys,” which, Hartley notes with some glee, beat “Electric Boogaloo” to market by three months, the feature documentary captures the high-stakes, low-taste atmosphere of Cannon’s anything goes approach to cinematic glory. Admirers of the company seal won’t need any coaxing to revisit the tripped-out visions of “Ninja III: The Domination,” “Invasion U.S.A.” and “Lifeforce,” but Hartley’s efforts are sure to mint new fans for one of exploitation cinema’s most prolific standard bearers.

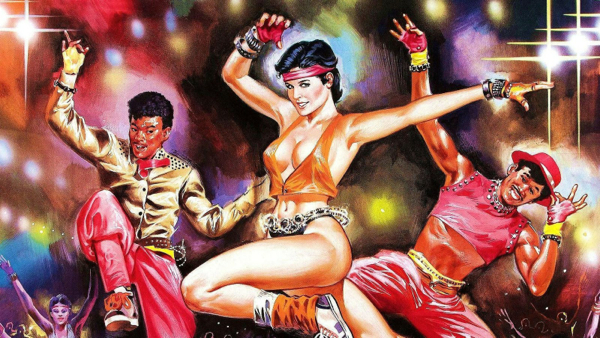

Emerging as a filmmaker in his native Israel after an adolescence spent obsessively attending the cinema several times a week, Golan produced Boaz Davidson’s wildly successful and influential “Lemon Popsicle,” the 1978 comedy-drama later remade as “The Last American Virgin” in the United States. Even though “Virgin” wasn’t a complete smash, in many ways it set the tone for Cannon’s more-is-more model, and Hartley makes an effort to touch on several subsequent productions that came to define the fast, cheap, and out of control ethos of Golan/Globus. The substantial return-on-investment hit “Breakin’” and its sequel “Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo” were released within eight months of each other.

With a few notable exceptions, it’s difficult to keep the interview subjects straight, since most of them pepper their recollections with impressions of Golan’s thick accent and bull-in-china-shop demeanor (one aspect of “Electric Boogaloo” that gets old). The resulting descriptions paint a Jekyll/Hyde mix of admiration and revulsion in the portrait of the garrulous Golan, whose outsize personality overshadows the more reserved and business-oriented Globus. Many attempt but few succeed in satisfactorily accounting for Golan’s wild miscalculations – obviously the man was not stupid, even if he had a tin ear for quality. Former MGM chief executive Frank Yablans might come the closest, shaking his head at Golan’s you-gotta-be-kidding-me Oscar hopes for the disastrous flop “Sahara.”

Despite the occasional stab at respectability – via unlikely partnerships with Jean-Luc Godard, John Cassavetes, and Franco Zeffirelli – Cannon’s bread was buttered by the twin obsessions of exploitation cinema: sex and violence. Hartley does not skimp on either, exploring the softcore sensations of Sylvia Kristel in “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” and “Mata Hari” and Bo Derek in “Bolero.” Several Cannon collaborators, including Derek, puzzle over Golan’s inexplicable, two-faced attitude with regard to films featuring significant sexuality and nudity, but that specific subject is never resolved in any detail. Neither is the period’s grim and casual predilection toward onscreen rape, a staple of Cannon director Michael Winner’s repugnant worldview as seen in the “Death Wish” sequels.

Hartley deserves credit for organizing what could so easily be a chaotic mess (several Cannon movies could sustain feature-length documentaries of their own) and for coherently communicating the hubris and overreach that led to the downfall of the company and the Golan/Globus split. The latter is summarized in a section that delivers the one-two punch of costly – for Cannon – movies that looked cheap: “Superman IV: The Quest for Peace” and “Masters of the Universe.” But even those failures have found a strange place in the pantheon of bad movies (some) people love, a category to which Cannon contributed an impressive share.