Movie reflection by Greg Carlson

As an unapologetic admirer of all things Prince, I for one was pretty grateful that “Under the Cherry Moon” was a radical departure from “Purple Rain.” Several years before “Graffiti Bridge” offered a sorta/kinda sequel to the 1984 smash, Prince – with enough earned clout and power to essentially do whatever he wanted to do – sent Mary Lambert packing (a shame) and busted out a black and white quasi-period fantasy that chilled the blood in most critics’ veins and bombed at the box office. Despite a few champions then – nobody will ever touch J. Hoberman’s brilliant original review – and even more now, Prince’s directorial debut is a tougher sell than the sweaty, throbbing first feature. For one thing, the phenomenal music is simply not as smoothly and thoroughly integrated into the narrative as the songs in “Purple Rain,” perhaps defiantly so.

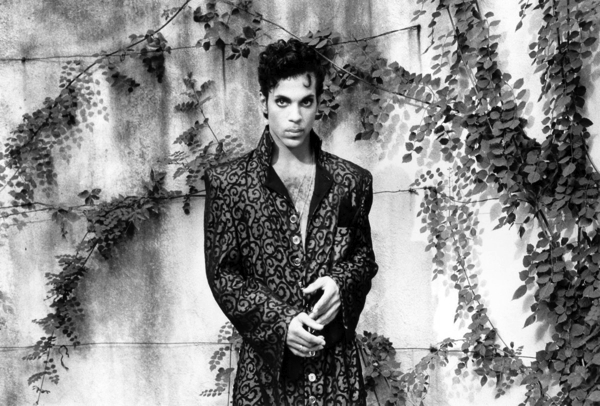

That’s no slam on the brilliance of “Parade” as an album or the welcome presence of composer/arranger Clare Fischer (who received the memorable credit thanking him “4 Making Brighter the Colors Black and White”), but I maintain that “Under the Cherry Moon” would have been much, much stronger had it included fully staged performances a la “Girls & Boys” instead of burying the music as background and extradiegetic score. Shot by the great Michael Ballhaus, who is so widely believed to have guided Prince during principal photography that the Internet Movie Database lists him as an uncredited director, “Under the Cherry Moon” has earned its cult status largely on the basis of Prince’s otherworldly screen image.

An entertainer in every sense of the word, Prince’s Christopher Tracy puts on one hell of a show. Inviting our gaze in and out of his unbelievable wardrobe, the number of eye rolls, double takes, nostril flares, and eyebrow raises merit any number of perverse drinking games. Jerome Benton’s comic timing in “Purple Rain” drew enough notice for Prince to poach him from the Time, and Benton largely repeats his sidekick function, playing Christopher’s partner in crime Tricky. In her screen debut, Kristin Scott Thomas appears as Mary Sharon, the woman who will inspire Christopher to abandon his occupation.

While neither “Purple Rain” nor “Under the Cherry Moon” boasts the most sophisticated dialogue scripting, the two films share in common several motifs, most prominently a love triangle to fuel some level of tension regarding the development of the inevitable romantic relationships that will favor Prince’s protagonists. While Apollonia could see through Morris Day’s silver-tongued lothario right along with the audience, it is far less clear whether Mary or Tricky resides at the center point of Christopher’s affections.

Close readings can support two seemingly incompatible arguments: that Christopher and Tricky derisively joke about and ridicule homosexuality or that the two men enjoy the kind of flower-petals-in-the-bathtub intimacy that suggests their roles as relocated Miami hustlers/gigolos swindling wealthy women on the French Riviera are constructed performances. The third option, of course, is that Christopher and Tricky, much like Monsieur Gustave H. in “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” are epicures with voracious omnisexual appetites. The suggestion of rent exchange ménage a trois payments is but one element of a subtext that, if pursued, represents a radical fearlessness for a figure as public as Prince in 1986.

“Under the Cherry Moon” is so batshit crazy, the presence of real bats driving a terrified Christopher and the other patrons from a restaurant makes perfect sense. As Old Hollywood glamour fantasia/melodrama, the movie name-checks Bela Lugosi, pays homage to “Casablanca,” and still accomplishes several of Prince’s ongoing career objectives blurring racial, gender, and sexual boundaries. That each of these occurs in relief to a class commentary adds another layer of interest.

Hoberman’s first paragraph ends by asserting, “The flaming creature who calls himself Prince may be the wittiest heterosexual clown since Mae West; black as well as campy, he’s even more threatening.” The rest of that essay is even better, and still ahead of the curve. I agree with Hoberman that the film’s Achilles heel is the frustrating tease (“all talk and no dancing”) of production numbers that never materialize, even though the heavenly performance of “Mountains” during the closing credits soothes a little of that sting.