Movie review by Greg Carlson

Following a work-in-progress premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, Brendan Mertens’ “Ghostheads” moves to Netflix to capitalize on the theatrical release of Paul Feig’s “Ghostbusters” reboot. Pitched to crowdfunders as a “documentary that explores the extreme side of Ghostbusters fandom, and looks back at the impact the franchise has had on the world over the past three decades,” Mertens’ film favors the former, exploring the cosplay subculture that devotes much time, energy, and money to proton packs and public appearances.

Despite talking head interviews with a sizable contingent from the original movie, including Dan Aykroyd, Ernie Hudson, Ivan Reitman, Sigourney Weaver, and William Atherton (sorry, but no Murray or Moranis), Mertens spends most of the time following the average folks who know the intricacies of class 5 free-roaming vapors and unlicensed nuclear accelerators. One Ghosthead, Tom Gebhardt of Keansburg, New Jersey, emerges as the movie’s de facto mouthpiece, articulating the philosophy of shared community and charitable giving embodied by Ghostheads across the United States, Canada, and regions beyond.

Gebhardt, like rabid devotee Peter Mosen and many of the other Ghostheads profiled by Mertens, speaks to the therapeutic aspects of fandom that in several cases have functioned as a safe haven for recovering addicts. Many of the on-camera interviews quickly bring tears to the eyes of the subjects, and Mertens labors, not always successfully, to strike a balance between the lighthearted and comedic components of the Ghosthead world and sentimental uplift that veers dangerously close to mawkishness.

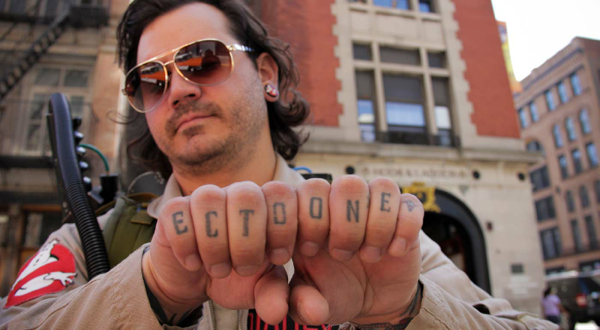

While it is tremendous fun to reconnect with the likes of Jennifer Runyon and Steven Tash (the students involved in Venkman’s electric shock ESP test) as well as check in with Ray Parker Jr. (who deserves a more thorough look at his hit theme song), Mertens takes a keener interest in the DIY everyperson willing to pursue “Ghostbusters”-themed marriage proposals or build screen-accurate replicas of the Ecto-1. The strongest argument on behalf of the true faith’s appeal lies in its egalitarianism: Ghosthead uniforms are most commonly and proudly adorned with the wearer’s own last name rather than the moniker of one of the fictional Ghostbusters.

Given the inventive design efforts that Ghosthead groups have poured into their geographically specific collectible patches, Mertens misses an opportunity to address the durability of the instantly recognizable international prohibition logo created by Michael C. Gross for the 1984 film. The simultaneous ubiquity and appeal of the so-called Icon Ghost (nicknamed Moogly by Reitman and Aykroyd) represents the gateway to “Ghostbusters,” and its fascinating history, which included a copyright infringement lawsuit filed by Harvey Cartoons against Columbia Pictures due to the character’s resemblance to Fatso of the Ghostly Trio, marks a key chapter in Tobin’s Spirit Guide.

It is difficult to say how much or to what extent Mertens knew about the misogynist and racist backlash against the new “Ghostbusters” during the production of “Ghostheads,” but his movie – which significantly exploits the timing of renewed enthusiasm in the franchise by interviewing Feig, visiting the NYC set, and showing a number of Ghostheads already emulating the costumes worn by the female squad in general and Kate McKinnon’s Jillian Holtzmann in particular – could have been a richer and more rewarding record had it taken that decidedly anti-Ghosthead issue into account.