Movie review by Greg Carlson

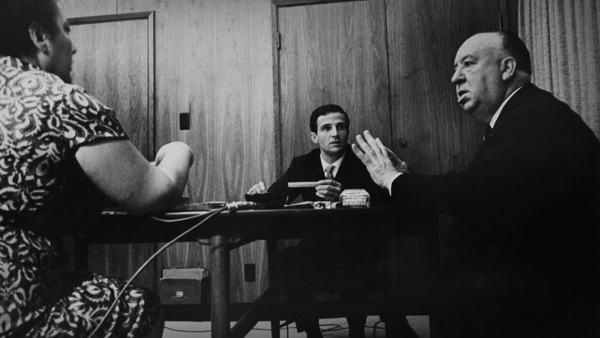

Finally making its way to HBO following a 2015 Cannes premiere and a festival run, Kent Jones’s “Hitchcock/Truffaut” (onscreen: “Hitchcock Truffaut”) demands attention from cinephiles of all ages. Bringing to life the 1966 book that emerged from a detailed series of face-to-face interviews conducted by Truffaut in Hollywood, Jones and co-scripter Serge Toubiana build a hagiographic monument to the filmmaker least in need of one. Even so, Jones makes a compelling case for Hitchcock’s lasting appeal as a master storyteller, and the tight documentary — which at 80 minutes will leave some salivating for more — serves as a visually engaging guide to one of the great directorial careers in motion picture history.

Crisply narrated by Bob Balaban (Mathieu Amalric in the French-language edition), “Hitchcock/Truffaut” cuts between key scenes from Hitchcock’s films — often accompanied by shrewdly selected audio clips from the 1962 meetings — and talking head interviews with a host of moviemakers inspired by the master’s techniques. Not surprisingly, Martin Scorsese and Peter Bogdanovich are on hand to offer anecdotes and perspectives. They are joined by Wes Anderson, David Fincher, Richard Linklater, Olivier Assayas, and others, who frequently annotate unforgettable moments from “Sabotage,” “Notorious,” “The Wrong Man,” and on and on.

“Hitchcock/Truffaut” is not without significant shortcomings. While Hitchcock’s most important collaborator, his spouse Alma Reville, earns a brief, perfunctory mention, not a single woman is included among the contemporary interview subjects. Kiyoshi Kurosawa is the only representative from outside America and Europe. Indispensable translator Helen Scott can be heard several times on the tapes, but unfortunately, we are offered no context for her key role in the original enterprise. By contrast, Robert Fischer’s “Monsieur Truffaut Meets Mr. Hitchcock,” in which terrific insights are shared by Madeleine Morgenstern, Hitchcock’s daughter Patricia, and Truffaut’s daughter Laura, accomplishes a more equitable representation of gender.

Another of the safe choices made by Jones is the emphasis placed in the second half of the film on “Vertigo” and “Psycho.” That two of Hitchcock’s most venerated movies feature prominently in the commentary is hardly a shock, especially given the longtime adoration of the pair by Hitchcock scholars and cineastes. The 2012 crowning of “Vertigo” in the number one spot on the Sight and Sound poll, which ended the fifty year record held by “Citizen Kane,” goes unmentioned in “Hitchcock/Truffaut,” but that “achievement” points to the unique position now held by the 1958 thriller. For the whetted appetite, Harrison Engle’s 1997 “Obsessed with Vertigo” makes a fine companion to Jones’s feature.

For the most devoted Hitchcock fans, Jones covers largely familiar territory. It is something of a welcome surprise, then, that the director deliberately omits explanations of the Bomb Theory and the MacGuffin, the latter of which is certainly a close cousin to Hitchcock’s fetishization of what Paul Schrader identifies as “dream objects,” those keys, handcuffs, ropes, lapel pins, and glasses of milk that, according to Assayas, may seem like minor details but “take a preeminent place” in the narrative, not unlike the way in which our own dreams govern what is important and what is not. In one delicious moment, Truffaut asks whether Hitchcock dreams much. The initial reply, in the negative, is only a surprise until Hitchcock slyly adds, “Daydreams, probably.”