Movie review by Greg Carlson

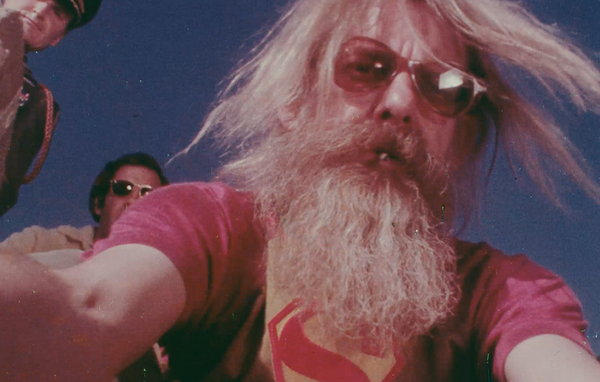

The career of legendary Hollywood iconoclast Hal Ashby is given a thorough assessment in “Hal,” one of this year’s several top-notch biographical documentaries and an absolute must-see for cinephiles. Making her feature debut as director, Amy Scott — whose own background as an editor closely aligns her with obsessive cutter Ashby — draws heavily from the research of Nick Dawson, author of “Being Hal Ashby: Life of a Hollywood Rebel.” The resulting film is a colorful portrait of an underappreciated master moviemaker whose marijuana-fueled, hippie sensibilities only enhanced the deep connection he felt to so many of the outsiders and dreamers who populated his films.

Scott is more interested in Ashby’s work than in his personal life, concentrating attention on the run of the filmmaker’s seven key movies of the 1970s, spanning from directorial debut “The Landlord” to the more-apt-than-ever “Being There.” The film does not, however, ignore Ashby’s prodigious appetite for drugs and his string of romantic partnerships that included five marriages. Scott strikes an effective balance between the public and the private, often acknowledging the intersection of the two in the ongoing battles waged between the filmmaker and the studio executives that Ashby viewed as nothing less than demons in tailored suits.

In addition to audio recordings of phone calls and conversations that allow the voice of Ashby to consistently represent himself as narrator, Scott invites Ben Foster to read excerpts from the letters that the director would furiously tap out to the objects of his love and his ire. Both Ashby’s words and his own voice complement the impressive lineup of luminaries who agreed to be interviewed for the film, and when unavailable for whatever reason, Scott draws on some terrific archival clips. Ruth Gordon, obviously, could not record and Bud Cort declined, but both are nicely represented in a vital section on “Harold and Maude” so tantalizing it could readily sustain its own full-length documentary.

Despite the cult devotion for “Harold and Maude” that would be sustained years later in the work of Ashby admirers like Wes Anderson (who landed Cort for the memorable role of bond company stooge Bob Ubell in “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou”), Scott furnishes solid segments on Ashby’s other essential movies. Both “The Last Detail” and “Coming Home” are discussed with a passion and verve that will inspire fresh visits to the films, and “Bound for Glory” and “Shampoo” are treated with appropriate insight and reverence. Through each, Scott illuminates Ashby’s maverick, anti-authoritarian ethos.

Along with his superhuman abilities at the controls of the motorized plates and rollers of the massive flatbed motion picture editing systems from which he could conjure magic, Ashby adored the characters brought to life by so many talented performers. Owen Gleiberman even asserts in his “Variety” review of “Hal” that Ashby was the “anti-Kubrick, treating each actor as the center of the universe.” Followers know that Ashby’s party ended with the dawn of the 1980s, and that chronologically arbitrary dividing line represents an eerily prophetic demarcation fixing the man firmly in time and place. Even though he made several more movies in the years before his death at the age of 59 from pancreatic cancer, Ashby no longer enjoyed the level of creative control that accompanied his staggering string of seven consecutive masterworks, but that initial septet is as good as the output of any filmmaker in the same period of time.