Interview by Greg Carlson

Kathleen Loock teaches American Studies and Media Studies at the University of Hannover. She writes about remakes, sequels, reboots, and seriality. Her recent publications include “Just When You Thought It Was Safe … : The Jaws Sequels,” “On the Realist Aesthetics of Digital De-Aging in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema,” and “Reboot, Requel, Legacyquel: Jurassic World and the Nostalgia Franchise.” Her video essay “Reproductive Futurism and the Politics of the Sequel” can be found here.

Greg Carlson: How did you get interested in movies?

Kathleen Loock: I was born and grew up in East Germany. I was nine when the Berlin Wall came down. So the typical American formative experience with film was not like mine. As far back as I can remember, I enjoyed movies. But I really started watching them seriously in my late teens and early 20s.

When I finished high school, I became an au pair for a year in Northbrook, Illinois. That’s when I started to go to the cinema regularly. I also got to know Blockbuster very well at that time.

GC: Was that your first visit to the United States?

KL: Yes. I applied for a scholarship to be an exchange student when I was fifteen and didn’t get it. So when I came a few years later, I went to the movies every week. Purchased a ticket for one show and then just stayed for the next movie and the movie after that.

GC: I can relate.

KL: It was also the first time I tried salty popcorn. That was not a thing in Germany. Unified Germany did have popcorn, but it was always sweet. Unsweetened popcorn was not introduced until much later, and there are still places where you can’t get salty popcorn. It took me some time to get used to butter and salt on popcorn, but I love it now.

GC: Do you remember the first movie you saw in the United States?

KL: I don’t, but I do remember this: I came in 1999 and had an orientation in New York. People were standing in line to watch “Run Lola Run.” I thought, “Americans are lined up to see a German movie?”

GC: I loved “Run Lola Run” so much that I went to see it on Friday. And then I went back to see it again on Saturday. And then one more time on Sunday.

KL: I never see a movie more than once in the cinema. But this phenomenon is part of what I study. Multiple viewings in the theatre is, of course, how films establish popularity.

GC: What movie makes you think of your time in America?

KL: “200 Cigarettes.” It left an impression on me and I haven’t seen it — or found it — since. I have looked for it from time to time with no luck. Another thing that struck me was how certain cable channels would repeat a movie multiple times a day or through a week. You turn on the TV and there it is. “Titanic” was on all the time. I always managed to turn it on when the ship was already sinking.

GC: Did your family have a VCR?

KL: My sister and I recorded movies on videotape. Often things we wanted to see that were going to be on too late for us to watch on a school night. Lots of horror.

GC: What were some of your taped treasures?

KL: Some of them scared me and my sister so much we didn’t look at horror for a long time. The 1990 version of Stephen King’s “It” and the 1989 version of “Pet Sematary” were two big ones. These were dubbed into German — the only way movies were shown on television at that time.

My parents got rid of that old VCR just a few weeks ago and many of our cassettes didn’t survive. I think “It” and “Pet Sematary” had been copied over a long time ago. I’ve been working on a video essay about “It.” When the remake came out, I was scared just watching the trailer. All the memories came back. Certain scenes were really present in my mind so I got the Blu-ray of the 1990 “It” and realized that my memories were just of the first ten minutes. After that, I had fast-forwarded to skip some of the scary parts.

GC: How did sequels, remakes, and series become the focus of your research?

KL: My dissertation was on Christopher Columbus, so I was already working with ideas of memory and repetition. I had taught a class on science fiction film around the time “The Invasion” came out. I got interested in the idea of film remakes because of that. Don Siegel’s 1956 “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” was followed by the 1978 Philip Kaufman version and Abel Ferrara’s 1993 “Body Snatchers.”

GC: The original is an all-time favorite. I watch it at least once a year.

KL: Yeah, and the 78 version is also great. It was so interesting for me to see how the remakes handled essentially the same story while adding something different. There is a kind of continuation of the larger story going on in the remakes. You can see the cultural anxieties change from one moment of film production to the next.

I organized a conference on remakes and co-edited a collection of essays in a book called “Film Remakes, Adaptations and Fan Productions: Remake/Remodel.” I wanted to know more. If you look at remakes, you have to look at sequels. So broadly, the repetition that exists in cinema is part of our lives and important to our memories. My own experience with “It” shows how films that return in some form bring back personal memories and influence the way we structure our own lives.

GC: Not long ago, I caught part of “Jaws 3-D” while it was playing on the monitors of a pub. The volume was all the way down. I kept sneaking glances at Bess Armstrong and Dennis Quaid and Lea Thompson and Louis Gossett, Jr. and started to wonder if it was time for a revisit. I last saw it in 1983 and have spent more than three and a half decades avoiding it.

KL: You should definitely revisit the “Jaws” sequels. A lot of people feel the way you do and don’t want anything to interfere with their memories and attachments to original films. But there is also a curiosity to see a story continue. Obviously, there is a tendency toward serialization, especially with television, that requires ongoing attention. With cinema, part of our interest in going back to older films is a way for us to revisit our own memories and feelings.

The new “Star Wars” sequels play with that kind of nostalgia. They want to attract viewers like you. And to accomplish that you cast original actors and make callbacks to the settings and to key props. That strategy is one way Hollywood studios can bridge generational gaps and develop new audiences.

I am curious to see “Ghostbusters: Afterlife.” Someone thought, OK, the previous reboot didn’t work, so let’s try a more nostalgic continuation that connects to the older movies as opposed to trying something completely new.

GC: What movie had such an impact on you that had to collect it?

KL: We definitely recorded on blank tapes more than we bought prerecorded movies. I was late to get a DVD player and to buy DVDs. I did watch certain Christmas movies multiple times. If a favorite movie happened to be playing on TV, I would watch it.

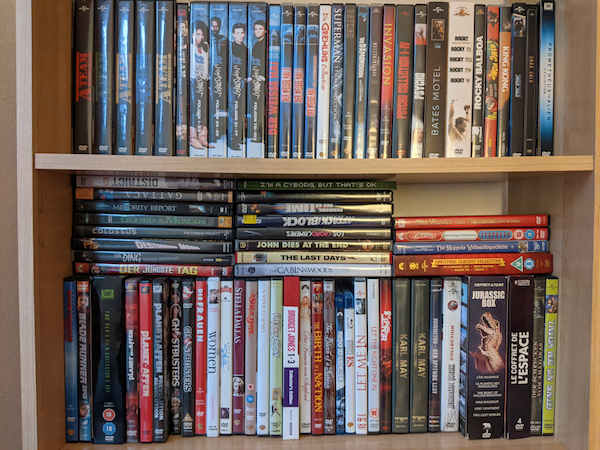

When I started this research project about ten years ago, I began buying DVD box sets. Rather than just buying “Jaws,” I wanted all four. Rather than just “Psycho,” I wanted one through four. I got an “Alien” set that orders the films starting with “Prometheus,” exchanging release chronology for narrative chronology. I am fascinated by how these kinds of films are packaged and sold.

GC: And when a movie is added to a series, like “Jurassic World: Dominion,” a new “complete” collection will be released.

KL: I have a “Rocky” set that does not include “Rocky Balboa,” “Creed” or “Creed II.” You have to keep renewing.

GC: Do you get more excited about sequels?

KL: Yes. With the pandemic, I haven’t been to the cinema in almost two years. But I am looking forward to “Ghostbusters: Afterlife,” “Dune” and “No Time to Die.” I am a little bit behind. I also follow production news and am interested in the way people talk about sequels, remakes, and reboots. Is there a sense that people are looking forward to them? Or are people critical of them? Using “Ghostbusters” as an example, there is this narrative that people feel relief about “Afterlife,” which is much more nostalgic.

GC: Lynch’s “Dune” is enjoying some positive reassessments. Do remakes cast a glow over originals?

KL: Films can become classics just because of the remake. The remake automatically focuses some attention on the original. With the 1978 “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” there was a look back at the 1956 film, which some had dismissed as “just” a B-movie. Looking at what has come before is part of the conversation. Inevitably, reviewers, critics, and scholars are going to bring up originals when they write about new versions or continuations. You can always look at the differences between an original and a remake to see how each speaks to its cultural moment. How does what came before still resonate now?

For so long, we have heard that remakes are unoriginal, are bad, are unimaginative. But they give us so much to think about.

GC: I love your essay on “Jaws.”

KL: I really enjoyed working on that. Thinking about what sequelization meant. The thinking about who is doing a sequel and why has changed over time. I worked with lots of newspaper clippings from the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and the Library of Congress. I also got to do some research at the Margaret Herrick Library. I looked through folders filled with clippings specifically on remakes and sequels. I was so happy and surprised to find them. You can’t find this specific material online. It doesn’t exist there.

I looked at debates and discussions that were going on at the time the sequels were being released. I am so intrigued by our desire to revisit fictional worlds and story worlds and the characters inhabiting those places. Recently, I read an interview with Villeneuve, who said he wanted to make a third “Blade Runner” film. And if he did, he wanted it to be free of Rick Deckard.

GC: How do you feel about retroactive continuity? For a brief moment, Darth Vader wasn’t anyone’s father.

KL: Any new chapter changes how we see the older ones. If a story goes on into the future, expansion must take place to some extent. Not only in terms of time and chronology but also in terms of characterization. “Blade Runner 2049” tries to continue the story more than it remakes or reboots the original. It centers on K more than on Deckard and introduces the “miracle child” plotline.

As for Darth Vader revealed as a father, the idea of generational family lines seems to pop up as soon as you start serializing. I don’t know if there’s a cure for retroactive continuity. Anytime you go forward, you add new layers of meaning to everything that has come before.

GC: Of all the series you have looked at, which one has the most satisfying continuation?

KL: Narratively, “Jurassic World” is really satisfying. Despite problems with gender and race, it really worked in the sense of relating back to the beginnings of the franchise. It returns to the first film to revisit the idea of the amusement park concept. It turns out we were waiting to see the park open to the public again.

GC: “Jurassic Park” will always be about that fence.

KL: Why would they try to open up again? Haven’t they learned anything? The hubris is strong: “We have the technology now. We can manage the dinosaurs this time.” I also liked the way that “Jurassic World” considered capitalism. To be sure, there were a lot of things that didn’t work in the film, but from the perspective of serialization, “Jurassic World” is more successful than “Blade Runner 2049,” which changed the meanings of “Blade Runner.”

GC: I went into “Blade Runner 2049” ready to dislike it. I was surprised by how much it won me over, in no small part due to the visual design.

KL: Visually, it’s a fantastic film. I did love to look at it. But I kept thinking about how it erased what we thought we knew about “Blade Runner” and Rick Deckard. For some people, replicants eventually being able to reproduce biologically is what would really make them “more human than human.” I found that off-putting.

GC: What is next for you?

KL: My new project is “Hollywood Memories.” We are interviewing people in different countries, including Germany, the United States, Mexico, and China. The focus is on the memories we have watching specific films and also on the life stages connected to our memories of certain films. I’m used to being the interviewer, so it was fun to be on the other side today.