Movie review by Greg Carlson

Next to the events that inspired it, Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s “Blackfish” is the worst kind of public relations nightmare for marine park giant SeaWorld Entertainment. Systematically documenting and dismantling years of questionable practices and dubious assertions about orcas, the gripping film uses an array of footage, from degraded old television spots to freshly composed interviews with scientists and former killer whale trainers. Most dramatic, however, are clips from several harrowing incidents in which the massive black and white captives have inflicted harm on one another and on human beings. SeaWorld representatives declined requests to be interviewed, and issued a rebuttal to some of the film’s charges.

The movie’s central non-human subject is a twelve thousand pound bull orca named Tilikum. On February 24, 2010, Tilikum killed 40-year-old SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau. The same orca was also previously involved in two other deaths: trainer Keltie Byrne in 1991 and Daniel Dukes in 1999. Although Tilikum has become one of the most widely known whales in captivity due to these three incidents, other captive orcas have killed trainers and there are dozens of well-documented near misses. In the wild, orca attacks on humans are nearly nonexistent.

A reasonable person might ask why Tilikum has continued to perform in SeaWorld shows after killing Dawn Brancheau and the answer, not surprisingly, is financial. Tilikum’s value as a stud is of tremendous significance to his owners. Motley Crue drummer and animal rights activist Tommy Lee – who does not appear in “Blackfish” – has called Tilikum the “chief sperm bank” of SeaWorld. Graphic video of trainers collecting whale semen underscores the exploitation, and the revelation that Tilikum is the most prolific sire in orca captivity leads Cowperthwaite to a deeper and more disturbing discussion of the cruelty of separating offspring from parent. Orca researchers know that killer whale calves remain with their mothers for life, and descriptions of desperate, long-distance cries as the young are taken by force leave a deep impression on the viewer.

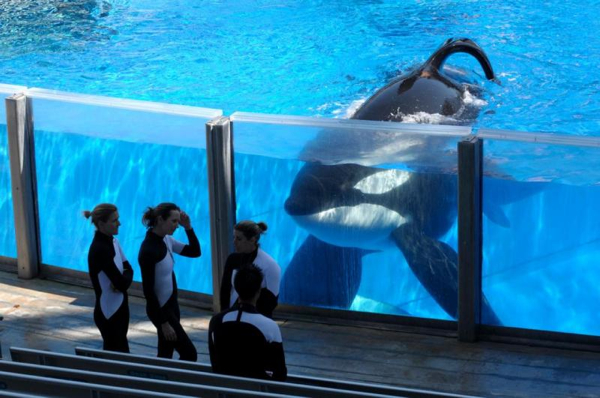

To be fair, SeaWorld does not break up all mother-offspring family units, but shrewdly, Cowperthwaite builds a case that exculpates the whales for presumably just responding to the appalling conditions in which they are forced to exist. In the wild, orcas swim many miles each day, and the cramped pens of SeaWorld in no way, shape, or form offer adequate room for the animals to thrive. Among the repercussions of cell-containment are behaviors in which whales rake one another with their teeth, dental problems from gnawing and chewing on barriers, and the most pathetic visual reminder of the difference between wild bull orcas and those in captivity: the collapsed dorsal fin. SeaWorld’s explanation for the numbers on flopped-over dorsal fins doesn’t align with scientific data.

The closest cinematic companion piece to “Blackfish” is probably “The Cove,” the gruesome expose of Dolphin hunting in Japan, but Cowperthwaite’s film also shares much in common with Werner Herzog’s phenomenal “Grizzly Man,” particularly in the way the ethics of human interaction with wild creatures are pondered. Interestingly, “Blackfish” omits any footage from “Free Willy,” although a few shots of Richard Harris in the much maligned 1977 “Jaws” pretender “Orca” are used to underscore some points about long-held misperceptions of killer whale behavior. Two other films are worth noting: “Blackfish” may lead some to Jacques Audiard’s “Rust and Bone,” one of the most memorable films of 2012. Also, Amy Kaufman reported in “The Los Angeles Times” a few weeks ago that the ending of Pixar’s upcoming “Finding Dory” was “retooled” following a screening and discussion of “Blackfish.”