Movie review by Greg Carlson

As reactions and reviews to Wes Anderson’s return to the world of Roald Dahl attest, the quartet of short story adaptations undoubtedly would have been better experienced as a theatrical omnibus akin to “The French Dispatch” rather than the one-a-day releases selected for streaming by Netflix, where the set now resides. At 40 minutes, “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” – which enjoyed a Venice Film Festival premiere at the beginning of September – holds pride of place as the leader and longest of the movies, but the briefer additions only enhance and expand the remarkable considerations of the increasingly brilliant Anderson.

The Dahl shorts join the mind-scrambling “Asteroid City” to make a strong argument that 2023 might just be Anderson’s most vital year to date. The director’s storytelling preoccupations have long entertained a fascination with the matryoshka of stories within stories and the intersection between the literary and the cinematic, even if those aspects receive less attention than the stylistic showmanship marked by mise-en-scène that is instantly recognizable to those who count themselves among the filmmaker’s faithful devotees.

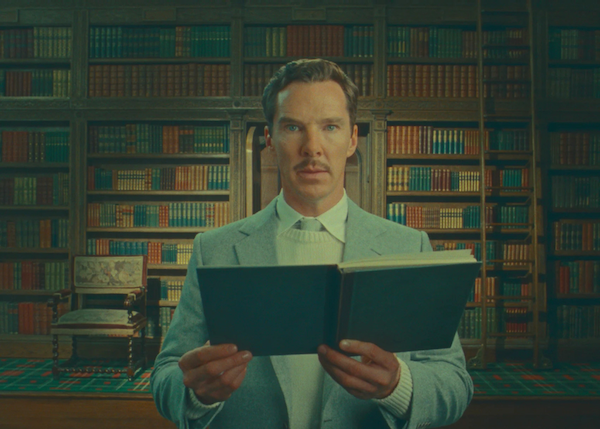

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” a deceptively simple moral fable about a man who comes to appreciate the joy of serving others, stars Benedict Cumberbatch as the title character, a fabulously wealthy gambler who learns a mystical technique that allows him to see without using his eyes. Joined by Ben Kingsley, Dev Patel and Richard Ayoade, Cumberbatch embraces the technical challenges set before him, presenting a multilayered blend of textual recitation (often straight from Dahl’s pages) directly addressed to the camera and facially expressive moments communicating the subtleties of what Bela Belasz described as the “polyphonic play of features.”

The chilling terror of “The Swan,” which also appeared in the 1977 short story collection headlined by “Sugar,” sharpens the focus of Anderson’s experiment. Adding Asa Jennings and Rupert Friend as child and grown-up representations of narrator Peter Watson, the recollection of traumatizing cruelty and bullying is rendered all the more powerful by the use of carefully choreographed pantomime and elision. Stagehands enter and exit the frame to deliver and retrieve various props, functioning as supreme exemplars of Brecht’s distancing effect, along with rear projection, forced perspective, and moving backdrops.

With the arrival of “The Rat Catcher,” Anderson leaves little doubt that his depiction of Dahl has come a long way from “Fantastic Mr. Fox.” Those reliable filmmaking hallmarks, including stop-motion animation and the perfect placement of miniatures and models, are joined by “invisible” elements and several clues hiding in plain sight that affirm a more sophisticated grasp of subtext. Ralph Fiennes, who also embodies the Dahl surrogate working in the unique hut/vardo of Gipsy House in framing devices for each of the four movies, plays the devoted, rodent-like exterminator sent to rid a hayrick of vermin. If we pay close attention, Anderson invites us to account for the failure of this grim pied piper.

It is perhaps the combination of the Rat Man and the frozen racist Harry Pope (Cumberbatch) of final short “Poison” that lights up the filament of Anderson’s unifying thesis, driving us toward a more nuanced consideration of Dahl. Writing for “Vulture,” Esther Zuckerman makes a bold claim that Anderson is now comfortable questioning the popular myths surrounding the author. Zuckerman reminds us of Dahl’s antisemitism before writing that the four films “make a case for the multitudes people contain: the capacity for wonder and kindness as well as unrepentant bigotry and meanness.” But how far is Anderson opening the door to new scrutiny?

Future essays by Anderson scholars will address all this and more. The absence of women can be blamed on the source material, but given Anderson’s boldness, would gender-blind casting for some roles have been out of line given Dahl’s other weaknesses? Along with that deficiency, Anderson will also be taken to task for what some perceive as the fetishizing/exoticizing of India first displayed in “The Darjeeling Limited.” Witnesses for the defense, however, will cite Anderson’s abiding Indo-cinephilia and a subtext critical of the colonizer as evidence to the contrary.