Movie review by Greg Carlson

A harrowing man-versus-nature adventure in the vein of a classic Reader’s Digest “Drama in Real Life” story, Danny Boyle’s “127 Hours” imagines the ordeal of mountaineer Aron Ralston, who amputated his right arm after being trapped by a boulder while exploring some narrow rock formations near Moab, Utah in 2003. While Ralston’s survival has been extensively documented on television, most notably in Dateline NBC’s “Desperate Days in Blue John Canyon,” Boyle’s movie is as exhilarating and indefatigable as any number of the filmmaker’s previous features, from “Trainspotting” to “Slumdog Millionaire.”

“127 Hours” is a precision-machined study in dialectical opposition: external reality battles internal fantasia, kinetic action collides with punishing immobility, and the threat of failure interlocks with soaring triumph. Director Boyle embraces these polar opposites with vigor, and even though the faint of heart have been warned via numerous publicity-enhancing accounts of possible lightheadedness or nausea brought on by the film’s graphic depiction of Ralston’s self-surgery, “127 Hours” transcends the grotesque through a relentlessly life affirming posture undoubtedly affected by the fact that Ralston made it out alive against overwhelming odds.

Adapted by Boyle and collaborator Simon Beaufoy from Ralston’s memoir “Between a Rock and a Hard Place,” “127 Hours” owes much of its visceral impact to James Franco’s performance as Ralston. Franco’s confident portrayal is certainly the best work of the young actor’s career, and he covers a huge range of emotional terrain without resorting to any significant traces of self-pity. Ralston’s initial sense of invincibility, forever erased by the 2003 experience, gives Franco a terrific platform from which to probe the character. Longtime admirers of the actor will not be surprised by Franco’s reserves of humor, manifested in a series of pitch black jokes laced with cosmic irony.

“127 Hours” is redolent of Sean Penn’s film of “Into the Wild” in the way that viewers are poised to vicariously witness the mettle-testing, life-altering, and mind-bending odysseys of principal characters from the safety of a darkened theater. Both Ralston and Christopher McCandless documented enough of their ordeals to provide the foundation for the “major” motion pictures that would eventually follow, and in the case of “127 Hours,” the presence of a small camcorder opens up a tantalizing world of possibility for Boyle, who uses it as a confessional, a time machine, and a last will and testament.

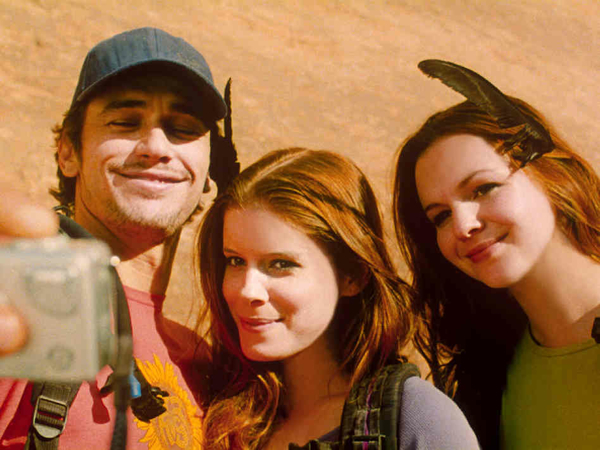

Ralston has attested to Boyle’s essential accuracy in the translation of his crucible, but it is worth noting that the film’s subject did not enjoy the secret pool frolic with hikers Megan McBride (Amber Tamblyn) and Kristi Moore (Kate Mara) prior to his accident. While the truth is less thrilling – Ralston demonstrated some basic climbing moves to his chance acquaintances before they parted ways – the swimming scene is revisited in a fascinating meditation that dares to flirt with erotic reverie despite, or possibly because of Ralston’s perch at death’s door. The enveloping presence of water, a major motif throughout the movie, provides one more example of Boyle’s deployment of contrasts, as Ralston’s own dwindling supply puts his life in jeopardy. By the end of the movie, if Boyle has been persuasive, the audience shares Aron Ralston’s thirst.