Interview by Greg Carlson

Filmmaker and educator Raymond Rea, who recently retired from Minnesota State University Moorhead, made an indelible impact on the Fargo-Moorhead film community.

In 2008, Rea arrived in Minnesota following years in San Francisco, where he taught at City College and San Francisco State University. Rea made his way to the West Coast from New York – where he studied with cinematographer Beda Bakta at NYU – by way of Ann Arbor. He also took classes from George Kuchar.

Rea is an accomplished moviemaker whose work has been screened in over 100 film festivals and exhibitions across the nation.

Our mutual friend and colleague Kyja Kristjansson-Nelson says, “Ray created space for both the community and our students to explore filmmaking and film viewing in all its forms, from the handmade, experimental and the hilariously perverse to grassroots community video projects that touched the lives of many of our local nonprofits and arts organizations. Ray leaves an incredible legacy here.”

Greg Carlson: When did film become important in your life?

RR: I can’t think of a time when film was not important to me. I grew up in Massachusetts, so if I wasn’t running around in the woods, I was watching movies.

GC: When you started making movies, were they strictly experimental or did you also tell traditional stories?

RR: I still have a few of the earliest shorts that I made on 16mm film. At the beginning, it was very low budget and very low tech. All the sound was added separately.

I would say these movies were experimental, but they were so short. One is only a minute and a half long. You certainly can tell a story in 90 seconds, but you would have to see them.

GC: Have you preserved and archived your work?

RR: I am trying. It is easier to archive the actual physical films in a can. What’s so damning about digital is that things can just go away. I try to keep up with external drives, but the evolving ports are a challenge. I have drives only a few years old that don’t easily connect to anything.

So many different formats have been used in my lifetime. I started in the era when everything was on film. In Ann Arbor, I did take the only video class offered at the time, which at that point was half-inch reel-to-reel. The deck was as big as a table. I needed a shopping cart to move the deck around and the camera was tethered to the recorder.

After that it was VHS and then Super VHS and three-quarter inch, and eventually Mini DV and DV CAM, but film was also making advances at the same time. There were better and better crystal-driven cameras.

GC: Film has been a constant for you.

RR: I didn’t even realize that until I was putting work together for an exhibition in Kansas City at Stray Cat Film Center. I have shot 16mm consistently over the course of many years. I also finished films on three-quarter inch that I have not transferred, but I did not finish anything on VHS. And I do have a number of digital projects.

GC: How do you encourage your students when they are adjusting to the steeper learning curve of working with film? We’ve all had rolls come back completely black.

RR: I’ve been there! And that’s what I tell them. I’ve made that same mistake. I ran one of the first 100-footers I loaded into a Bolex all the way through with the shutter closed when I was in my early 20s. You learn to just move on.

We were used to these kinds of things happening in still photography. We were accustomed to the idea of taking your film to the photomat or sending it to a lab and waiting for it to be developed. So it didn’t seem so different when we did the same thing with motion picture film.

If there is one difference in the students of today, they are so pissed off when it’s not instantaneous. They want the luxury of immediately seeing what they shot. I address that with students – waiting to see what you’ve done can feel excruciating, but it’s part of filmmaking.

GC: Is the Bolex your favorite 16mm camera?

RR: Well, I own a Bolex, so it’s my go-to.

GC: My friends and I used an Eclair for a lot of our movies.

RR: That’s crystal-driven, so you can do synchronous dialogue. When I teach the Bolex face-to-face, I spend time on the loading process. We use daylight spools, which means you are relatively safe from accidental exposure. At first, we spend time practicing in subdued light with dummy loads and then I say, “OK, now we’ll try it in total darkness and this is where the rubber meets the road.”

One of my first jobs on a 35mm set was as a loader, so I got a ton of practice in complete darkness. Loading is an entry-level job on a camera crew, so I tell students that it is valuable to learn how to load. And to load in the dark.

GC: What film is important for you to show to students?

RR: I really like “The American Astronaut” by Cory McAbee. I would say it’s surreal – very imaginative. All shot on black and white film. It can be hard to describe, but I would use the word fun. I tried to bring McAbee to campus, but it never worked out.

Each time I show it, there is usually one student who approaches me to borrow the movie or ask how to get a copy.

GC: That’s a rewarding feeling, isn’t it?

RR: Yes. Another film that I show to beginners is Jean Cocteau’s “Orpheus,” because it has so many in-camera special effects. Like going through the mirror or falling down the wall – so many amazing ideas that are so poetic.

GC: It leaves an impression. And makes you seek out other similar works and surrealist films.

RR: I had a really good theater and film professor in high school who hosted movie nights. He showed “The Blood of a Poet” and that inspired me so much. I’m older than you but I’m not that old. My mom and my dad are from the New York City area and that’s where they grew up. We were in New York City once and they took me to see “2001: A Space Odyssey” in 70mm. I was a kid but I remember being just overwhelmed – and loving it at the same time.

GC: To prepare for your move, I know you have been downsizing. Did you decide to keep any favorite movies?

RR: Yes, but very few. I have never held on to a large collection of movies. When I was in San Francisco, during the peak of the VHS era, I taught as an adjunct. There were several utterly amazing movie rental stores that I frequented. I used those places as resources, consistently renting movies I needed to see. San Francisco State University had an excellent 16mm and VHS collection.

When DVD took over, I put together a collection of movies for my queer film history class. I am bringing those movies with me.

GC: Which films in that collection surprise you the most in terms of student response? Did you switch titles in and out of rotation?

RR: I always felt like I probably should have done more of that. I start the course by saying that the topic is so vast and so broad an umbrella, many movies are bound to be left out. I show a pair of 1961 films: “Victim” by Basil Dearden and “The Children’s Hour” by William Wyler.

GC: Along with studio films, do you include independent and outsider films?

RR: Yes. I move chronologically, so I show Leontine Sagan’s “Mädchen in Uniform” near the beginning. Later in the class, I show things like Kenneth Anger’s experimental short “Kustom Kar Kommandos.” When I taught the class in San Francisco, I showed some Curt McDowell films – he was a contemporary of the Kuchars.

GC: “The Celluloid Closet” – both the book and the documentary – was the first time I really thought about queer cinema.

RR: I use a few chapters from “The Celluloid Closet” in class. In the book, Vito Russo does a lot of name-dropping. It can feel like a wave of fifty or more film titles coming at you on each page. He had an incredible wealth of knowledge about that subject. I think the movie version is great as well.

They do an excellent job with coding. I love the inclusion in “The Celluloid Closet” of the famous clip from “Red River” where cowboys Montgomery Clift and John Ireland compare and handle their guns. I like to show that scene and one from “Rebecca” and a couple others. For students who have had no prior exposure to queer film, these can be eye-opening.

I talk about the Hays Code in that class and I am sometimes surprised that students haven’t heard much, if anything, about it. To me, as a cinephile, those restrictions represent such a large portion of what happened in this country.

GC: Some students grew up watching anything they wanted to see while others had parents who limited and filtered content. Young filmmakers in every generation emulate the trendiest and hottest directors at the time.

RR: Yes, and over time you can see how transient those influences can be. Tarantino starting in the 90s, and then when I first moved here I saw a lot of movies inspired by Christopher Nolan. In the last couple years, Nolan faded as an influence and I was baffled by that. Nolan may still be huge, but he is not “the guy” any longer for young students.

GC: As a creative artist, who were the filmmakers you most admired when you were younger?

RR: Martin Scorsese. The first movie of his that I saw was “Taxi Driver” and then later I discovered “Mean Streets” and thought, “This might be even better!” Spike Lee’s early films, including “She’s Gotta Have It.” Lizzie Borden’s “Born in Flames” and “Working Girls.”

I worked briefly at the Bleecker Street Cinema and there was just so much to see in New York.

GC: Your retirement marks the end of a chapter in the local film scene. How do you think things have changed since you first arrived here?

RR: I think I am okay at starting things, but I’m really terrible at sustaining things. So it is good that I am not in charge of the FM LGBT Film Festival anymore. It will grow and continue. Festival programming can be a chore and at first I was trying to do so much of the organizational stuff. I knew when I handed it off to Sean Coffman that he would do amazing things with the festival. And now Sean will pass the torch to Sean Collins, who intends to develop local talent from within the FM community to take over.

I knew that I would be leaving the area once I retired and I wanted the festival to fly without me. I think it will do that.

GC: Now that your boxes are packed, did any other movies make the cut?

RR: Yes. I love Fassbinder’s “Fox and His Friends” and “Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.”

When people ask me to name my favorite film, though, I usually say “To Have and Have Not,” even though I feel like that is an impossible question to answer. That movie is not experimental. It’s traditional and has a straightforward narrative thrust.

I remember in high school going to a friend’s house and seeing “To Have and Have Not.” I was part of a gang of girls at that point in my life. Some of the others may have thought it was just an old movie, but I was stunned by Lauren Bacall. She was my first celebrity crush, specifically in that film.

GC: I also adore “The Big Sleep” so much. Not only Bacall and Bogart, but Martha Vickers and Dorothy Malone!

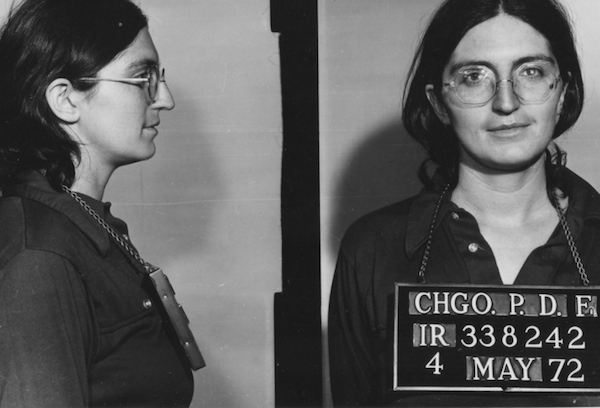

RR: I love that film and the novel. I am really a fan of nearly all Raymond Chandler. When I officially changed my name, I had been Rae for awhile, and that was not even my original name. Changing the spelling of Rae to Ray was pretty simple, but A: I wanted to give myself an extra syllable and B: I was a huge Raymond Chandler fan.

It was up to me to name myself. Nobody was going to do it for me.