Interview by Greg Carlson

Conor Holt works in television post-production in Los Angeles and has scoured almost every video store and thrift shop in Los Angeles County on an endless quest for VHS cassettes. This spring he finally made the trek to Bend, Oregon to visit the last Blockbuster in the world.

Greg Carlson: When did you fall in love with the movies?

Conor Holt: Since I’m a 90s kid, I grew up with VHS tapes in the house and home video was always part of my life. I don’t remember life before home video. I watched “Aladdin” more than any other movie.

I would go to the video store with family and then with friends. There is that criticism that Blockbuster and Hollywood Video killed mom and pop shops. For some people, there weren’t any nearby mom and pop stores. Back then, I didn’t even know they existed. All I had was Blockbuster and Hollywood Video.

GC: And there’s a parallel to movie theatres.

CH: Of course, I love going to places like the Fargo Theatre, or here in L.A. the Vista or the ArcLight. But in many communities, you might be limited to AMC or a similar multiplex. I support cinemas no matter where they are.

GC: I like your attitude. The library was also a place that helped me get into movies. Some of my first experiences with classic monsters like Dracula, King Kong, Godzilla, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon were courtesy of the orange Crestwood House books.

CH: I love the library. Hollywood Video only had a small classics section. When I was in high school, I got Roger Ebert’s “The Great Movies” and I got “1001 Movies to See Before You Die.” I went to the library to track down a lot of those films, like “Rashomon” or Orson Welles’s “Othello,” because I couldn’t find them at the video store. That practice continued into college. Thank goodness for libraries.

GC: What was the movie that made you decide to pursue a life in film?

CH: One of them is Robert Rodriguez’s “El Mariachi.” I saw it at the right age. And it had all those perfect components: he made it on a tiny budget and worked with friends and family. And then built that into a career. So it was very inspirational. You don’t need millions of dollars to make a movie. As long as you have access to a camera, some supportive collaborators, and the creativity and will to do it, you can make something good.

The audio commentary on the DVD — one of the most valuable features of owning physical media — was and is huge for me. The best commentaries just bring you into a film and teach you so much.

GC: The “El Mariachi” commentary and “Rebel Without a Crew” inspired so many future filmmakers. What was the first movie you acquired on your own?

CH: Along with the Rodriguez Mexico Trilogy, “El Mariachi,” “Desperado” and “Once Upon a Time in Mexico,” I also got “Memento.” The special edition DVD in the packaging that looked like a hospital chart folder. The design of the menu navigation was brilliant. They went all in on that one.

GC: Are there other cinephiles in your family?

CH: We always liked watching movies together. If you go to my parents’ house, the VHS tapes are still there. The childhood collection has not changed, beyond the addition of a few titles, in twenty years.

When I was in high school, I took a summer class about filmmaking. The class inspired me to explore new movies and one thing led to another. Add that to the books I mentioned and it was all a step-by-step process. Luckily, I had some like-minded friends.

One of my favorite high school memories was buying tapes at Hollywood Video when they liquidated VHS for a dollar per tape. We biked down there and we each bought a dozen movies or so. I still have those tapes in my collection. “Nosferatu” and “City Lights” were in that group, and they are precious to me because the cases still have the Hollywood Video location stickers. The store is gone and I can’t even find a photograph of it anywhere online, but I have the tapes with the stickers that prove it existed.

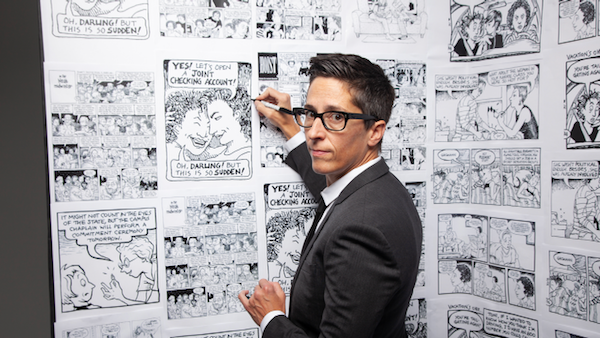

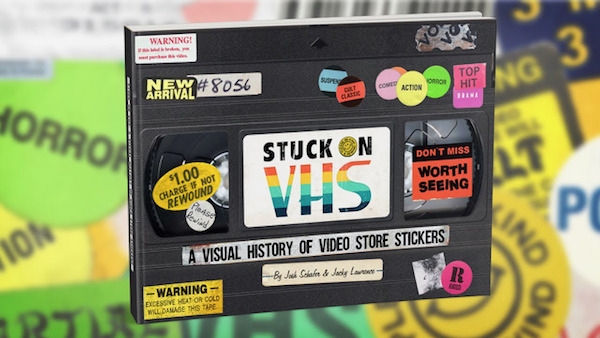

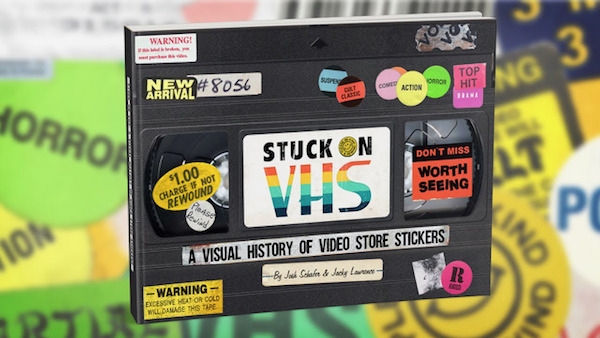

GC: Speaking of stickers, you contributed to the Birth.Movies.Death book “Stuck on VHS: A Visual History of Video Store Stickers.”

CH: I was following Josh Schafer, one of the co-authors of the book and the editor of “Lunchmeat VHS.” He was posting about plans for the publication, so I searched through my collection and shared the most interesting stickers. I think the project turned out beautifully. It’s a wonderful collection of art. So much nostalgia that brings back memories, especially the weird or fun ones, like the “Bee Kind Rewind” with the bumblebee illustration.

Sometimes, that Video Hut or Video Palace sticker is the only remnant of a place that no longer exists.

GC: Video store stickers make me think of genres. What are your favorites?

CH: Science fiction. Especially indie or smaller scale sci-fi. I love Spike Jonze’s “Her.” I love the Richard Schenkman/Jerome Bixby collaboration “The Man from Earth,” about a professor who claims to be immortal. I enjoy big spectacle as well, but I like the way a thought-provoking, small-budget movie can get in your brain.

GC: I know you are an animation fan.

CH: I love animation. They can be so beautiful, so wondrous. And they cover so many genres and storytelling techniques from all over the world. Animation still does not get the respect it deserves. I am always happy when an unexpected animated film breaks out to a wider audience.

GC: What is your most-watched animated film?

CH: Probably “Aladdin,” but the turning point for me was “Princess Mononoke,” which I saw when I was in high school. It was my introduction to Studio Ghibli, which turned into one of my greatest passions. I return to “Mononoke” again and again. It’s incredible.

GC: What is it about Miyazaki and Ghibli that speaks to you?

CH: On one hand, Ghibli films are not quite mainstream in the United States, even though they are probably the best-known or closest thing to mainstream anime here. There’s a lightness to their movies, a certain nuance to the films that is special to me. Of course these stories have a beginning, middle and end, but they feel alive to me. And outside of plot, they have the ability to convey a moment in time.

Many of the endings of Miyazaki’s films feel ambiguous. They are still satisfying, but to me, it isn’t “That’s it. That’s the end.” I feel like the characters live on, like real people, beyond the frames of the movies. We just glimpsed a small part, a window of time, and the film exists on another plane, with more stories that we haven’t yet seen.

GC: What did you think about “Earwig and the Witch”?

CH: I like it, but it’s definitely not their best. Not enough story there. The attempt to try CG animation was a bit rough, a bit rocky. However, I appreciate taking new chances and trying new things. The ending felt a little too short. Goro Miyazaki’s previous film, “From Up on Poppy Hill,” was really terrific.

GC: I am always attracted to stories featuring witches and witchcraft, but I agree with your comments. What are some other ways you focus your viewing habits?

CH: I am still in the mindset of “1001 Movies to See Before You Die.” I’ll think, “I haven’t seen a silent film in a few weeks, so I better remedy that.” Or, “I haven’t seen a musical in awhile, what should I check out?” And then I can cross “Sunrise” and “Flower Drum Song” off my list.

I am always striving to diversify and seek out stuff that is new and different to me. I am always open to trying new genres. Horror is so popular in the VHS community. Lately, I have been digging into more underground, grindhouse, and shot-on-video stuff. I finally watched “Video Violence” and had a lot of fun.

GC: I’ll watch anything at least once. Do you collect in multiple formats?

CH: Right now, I keep over 1000 VHS tapes. Probably another 600 or so DVDs and Blu-rays. I love the format, the aesthetic, and the nostalgia of VHS, though. And the fact that there are so many movies that are available only on VHS. I like curating my own personal museum.

Scarecrow and Vidiots preserve some rare copies, sometimes just one copy. So I always think I better hang on to mine just in case.

GC: What items have pride of place in your collection?

CH: The tapes from Hollywood Video that I mentioned earlier. Some tapes from a local video store here in L.A. called Odyssey Video that closed a few years ago. Lots of anime tapes. Some older anime is rare on physical media. I am interested in different versions, different box art. Miyazaki’s “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” was released on VHS in the United States as “Warriors of the Wind” in a truncated version. I like having that edition on VHS, since it will never come to DVD or Blu-ray. It’s interesting to have that artifact. As a kid in 1988, that was the only way to be able to watch it.

When I hold a VHS tape made in the 70s, 80s, or 90s, it’s like a time loop. This thing existed 20 or 30 or more years ago. Holding it in my hand, I get the sense that if I had been a teenager back then, this is what I would have watched. So I feel connected to an earlier time period.

GC: Aside from the industry, what drew you to Los Angeles?

CH: I moved to California after I finished undergrad. I did a couple internships to get started, including one at Marvel Studios in 2013. As a P.A., I ran errands and helped out in the office, but I also got to help in the research department, reading comic books to look for scenes and images to build portfolios. I got to go to Comic-Con when I was at Marvel, which was an amazing experience.

I worked odd jobs until I was able to do post-production. I am currently an assistant editor on television shows. I am glad to be working in production, because it can be tough to get into that world.

Over the past eight years, I have fallen in love with the city and its history, culture, and community. Every year, I try to visit new spots. Especially bookstores and record stores.

GC: You just shared a post about finding some great film noir locations.

CH: Yes, the house from “Double Indemnity,” up in the hills overlooking the city. One of the houses in “Chinatown.” Someone, of course, lives there and I hope they appreciate owning a house from one of the great movies! Houses from “In a Lonely Place” and “The Long Goodbye,” as well. It is fun to find those landmarks.

Charlie Chaplin’s “The Kid” turned 100 this year. The street from the final scene in the movie hasn’t changed all that much in a century. I found the plaque there, marking it. You can stand on the cobblestones on the street where Chaplin made part of “The Kid.” It’s so exciting to be able to do that.

GC: How do you keep your collection organized?

CH: I have a small bed, so I can maximize space! I have tried to downsize the collection, but it doesn’t work. I had stuff everywhere, so I did get some new shelves during the pandemic. I have so many weird items, like comedy specials, commercial videos, educational films — the only release versions that will ever exist. If I get rid of them, I will never be able to see them again.

I don’t even mind the limitations of VHS, like pan and scan. Obviously, if I love a film I will want to see it in the original theatrical aspect ratio, but it doesn’t ruin a film for me to watch it on VHS. VHS reminds me of being a kid, and that is what all movies looked like to me then.

GC: How do you decide what to buy?

CH: I like exploring all the boutique label offerings, including international labels. Criterion is still number one, but there are now so many Criterion-esque options it can be tough keeping track of it all. Having a region-free player is the key to unlocking so much great stuff.

GC: What movies do you keep in multiple editions?

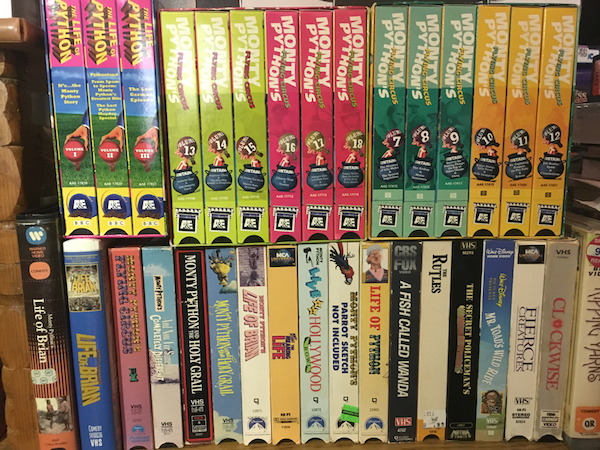

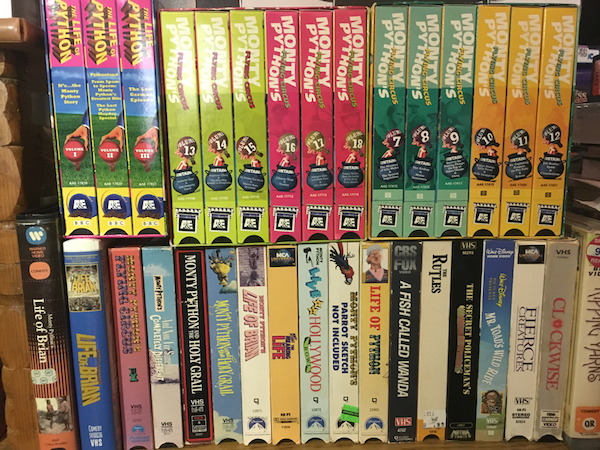

CH: The Ghibli films and Monty Python. I have them all on VHS, as well as related works like “A Fish Called Wanda.” It’s not Python, but two of them are in it. The TV show “Ripping Yarns” that Palin and Jones did. I like their comedy albums on vinyl, which I also collect. I hope to eventually have every single thing that they released, so that is a collecting goal of mine.

GC: What is the funniest Python moment?

CH: It has to be something from “Monty Python and the Holy Grail.” It was the first one I saw. The one I really grew up with. I love the opening credits. My dad and I quote it back and forth. I have a pair of coconuts signed by Eric Idle. Monty Python and Studio Ghibli are very different things, but both are equally important in my life.