Movie review by Greg Carlson

Tim Wardle’s documentary “Three Identical Strangers” shares the seemingly impossible tale of brothers Eddy Galland, David Kellman, and Bobby Shafran, separated-at-birth triplets who discovered one another as young adults in 1980. Recipient of the U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award for Storytelling shortly after its world premiere at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, the movie draws on new interviews and a strong archive of visual material to paint a colorful but troubling picture of a secret study that aimed in part to gather information about nature versus nurture.

At the age of 19, Shafran showed up at Sullivan County Community College in New York to an utterly surreal welcome, as people he had never met greeted him with warm hugs and kisses. He quickly realized the students had mistaken him for someone named Eddy, and a visit with one of his doppelganger’s friends arrived at the strange truth. Eddy and Bobby met face to face in Long Island and local and regional media interest followed the long-odds discovery. And then, an even bigger bombshell detonated as David spotted an article on the siblings and recognized himself. Another meeting and the Three Musketeers were off to the races.

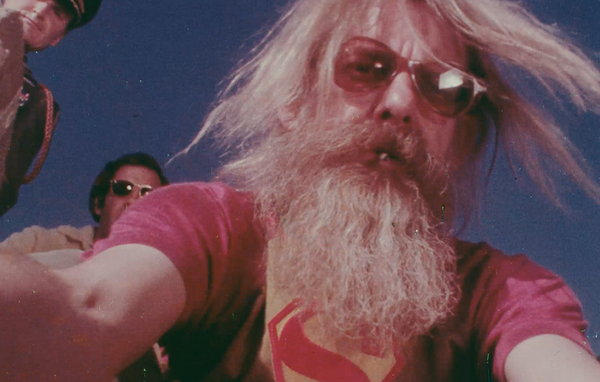

Reconstructing certain key events with dramatized flashbacks, Wardle gets much more mileage from the energetic section following the pre-internet celebrity of the brothers as they dazzle and delight on talk shows and in magazine articles. Playing up their “uncanny” similarities (same smokes, same taste in women, same key interests, etc.), the fellows pour on the charm with matching mannerisms, matching outfits and hairdos, and matching smiles. Madonna invites them to make a cameo in “Desperately Seeking Susan.” They party at the Copa and Studio 54. They open their signature SoHo restaurant Triplet’s and capitalize on the perfect combination of extroverted bonhomie and heartwarming human interest that draws booming business.

But the good times don’t last. Tragedy looms along with the nasty truth surrounding the circumstances of the adoptions. The roller coaster of emotional swings inherent in the story presents Wardle with a narrative conundrum that splits the film with a tonal challenge of communicating the extent of the joy and the pain. Beginning with the weird thrill and jubilance of the unexpected reunion and ending with the grim mystery of the unethical experiment that split up the brothers in the first place, Wardle shifts from the rapid-fire montage illustrating brotherly love to the tearful nightmare initiated by Viola Bernard and Peter Neubauer and facilitated through adoption agency Louise Wise Services.

“Three Identical Strangers” also hints at more subplots and characters than the length will sustain. The boys were carefully placed with parents that had already adopted an older daughter. One family was working class, one was middle class, and one was well-heeled. None were told of the existence of the other two boys. Especially tantalizing is the supporting appearance of Paula Bernstein and Elyse Schein, authors of the memoir “Identical Strangers” and unwitting participants in the same set of research. Viewers eager to learn more may wish to seek out Lori Shineski’s 2017 film “The Twinning Reaction,” which also explores the same study.