Movie review by Greg Carlson

Following a 2023 South by Southwest world premiere, writer/director/star Leah McKendrick’s “Scrambled” gets a well-deserved theatrical run in U.S. cinemas. The busy and talented moviemaker, whose online presence in projects like the series “Destroy the Alpha Gammas” and the short Poison Ivy origin story “Pamela & Ivy” earned critical acclaim and caught the eye of Sony Pictures (among others), draws from her own experiences with egg retrieval in her new feature. Simultaneously a raucous, whip-smart comedy and a feminist treatise on self-image, self-actualization, and self-love, “Scrambled” has a heart as big as the laughs it consistently generates.

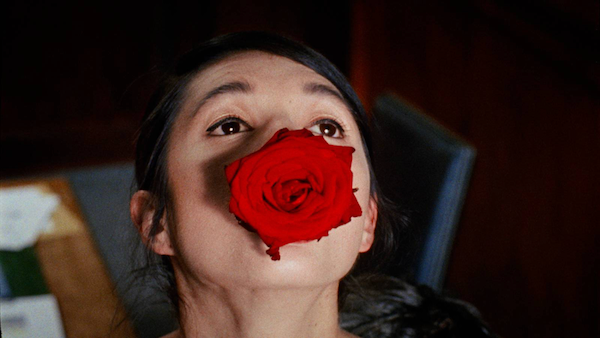

McKendrick plays Nellie Robinson, a woefully underemployed 34-year-old who feels like she’s running out of time to match the milestones of the peers inviting her to what seems like a nonstop celebration of engagements, weddings, baby showers, and birthday parties. Following pal Sheila’s (Ego Nwadim) nuptials, which inaugurate the movie with a hysterical cascade of rapid-fire gags alongside all the necessary exposition, Nellie decides to undergo the oocyte cryopreservation process. Borrowing funds from her financially successful brother Jesse (Andrew Santino), who perhaps attaches too many strings to the deal, Nellie starts a series of appointments with a deadpan and occasionally inappropriate doctor (a terrific Feodor Chin).

And if the painful abdomen injections aren’t enough, Nellie also embarks on a quest of hook-ups hoping to recapture some of the spark she briefly enjoyed with “The One (That Got Away).” Each of the doomed encounters is accompanied by an onscreen title (“The Cult Leader,” “The Nice Guy,” “The Prom King,” etc.) suggesting some character trait that summarizes romantic suitability or the lack thereof. When asked whether she is seeing anyone, Nellie’s reply is “I’m seeing everyone.” None of the prospects, however, click with our heroine, who faces additional pressure from the members of her family. The nuclear unit reminds Nellie (and us) of protracted childhood dependency.

Nellie’s father is played by Clancy Brown, who is just as good in the role of a gruff patriarch with a hidden heart of gold as he is inhabiting terrifying villains. Brown’s cluelessness as he perpetually manages to say the wrong thing at the wrong time finds a hilarious partnership with Santino. McKendrick the screenwriter has enough confidence to spread the best lines around. Her slow-burn reactions to insults lobbed by Brown and Santino add layers to Nellie. Many critics have identified the ways in which “Scrambled” walks and talks like a scripted television series. That may be true, but the style is not necessarily a liability or a shortcoming.

McKendrick doesn’t always find the perfect balance between horny comic hijinks and warm-hug affirmations (I prefer moments like the insistent, borderline cringe, pre-wedding dance review of the proper order of hand jive operations so that Nellie and her partner can make a memorable, if desperate, “Grease”-inspired entrance). The movie has at least one too many scenes in which Nellie pours out her heart in an act of brave vulnerability. Those monologues, however, are worth it as long as we also get to spend so much time with Nellie at her messy, embarrassing, free-spirited best.