Interview by Greg Carlson

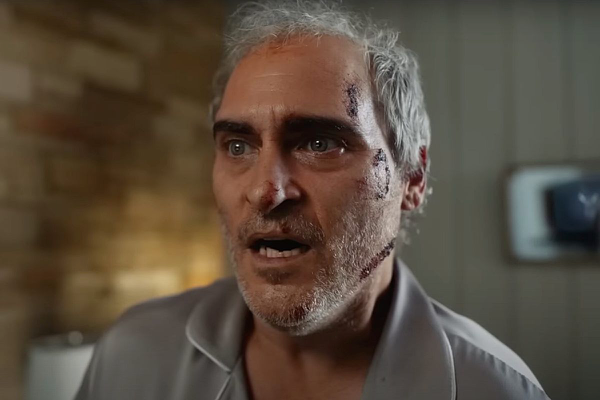

On Saturday, March 25, filmmaker Mike Flanagan returns to the Fargo Film Festival, where “Absentia,” his debut feature, made its world premiere in 2011. This time, he will be joined by his wife and regular collaborator Kate Siegel to talk about projects including “Hush,” “The Haunting of Hill House,” “The Haunting of Bly Manor,” “Midnight Mass,” and others. Flanagan and Siegel will receive the Ted M. Larson Award, the festival’s highest honor.

Tickets for “An Evening With Mike Flanagan and Kate Siegel” are available at the Fargo Theatre box office.

Greg Carlson: What was the first movie that left a big impression on you?

Mike Flanagan: The first movie that I remember seeing that had a big impact on me was “Jaws.” That was probably the most influential movie for me. I feel like I watched it 100 times while I was growing up. I learned about filmmaking from that movie. As I got older, I appreciated different aspects of cinema by studying it.

I first saw “Jaws” on a pan-and-scan VHS tape and then later on a letterboxed LaserDisc. Suddenly, it was a different movie when I could see the whole frame. That difference alone helped me understand aspect ratios. I was one of the many who erroneously believed that if I saw black bars on the top and bottom of my screen it meant that part of the picture had been removed, and not the other way around.

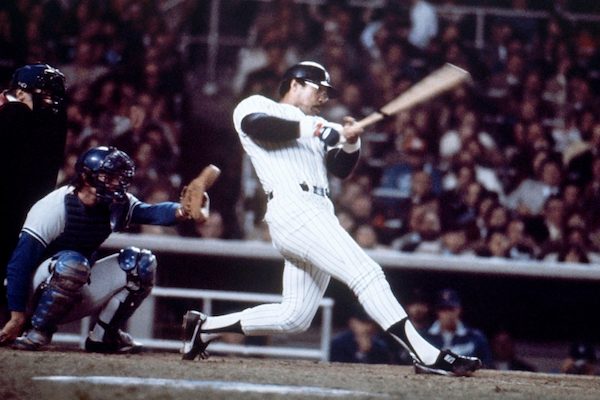

Thanks to DVD and Blu-ray, I got to learn even more about the process of moviemaking, becoming more aware of how to make a film through those repeat viewings. “Casablanca” was another hugely influential film for me when I was growing up. But I really got serious about wanting to make movies after I saw Brian De Palma’s “The Untouchables.”

The first movie I made, shot on VHS in my backyard with my friends, was a remake of “The Untouchables.”

GC: Fantastic. Was this a truncated version or a shot-for-shot remake like the “Raiders of the Lost Ark” adaptation by Eric Zala, Chris Strompolos and Jayson Lamb?

MF: I think it was about a 25-minute movie, but it did tell the whole story. We included whatever we could get away with shooting in my family’s house. I played Elliot Ness. We went through all the major story beats of the feature. Our film wasn’t nearly as sophisticated as the “Raiders” adaptation.

GC: Did you see lots of movies in the theater when you were growing up?

MF: Going to the movies was a great way for my family to get my younger brother and me to relax. The go-to was the Cineplex Odeon at the Market Place Mall in Bowie, Maryland. We could ride our bikes there. It was a six-screen theater that eventually became my first job. I started working there in concessions when I was 15 and stayed until I was 22. Working at a theater taught me a lot about the exhibition of movies. I learned projection. And I learned about film composers by listening to credits while I cleaned the auditoriums.

GC: When I worked at the Century in Fargo, I listened to “The Little Mermaid” and “The Silence of the Lambs” dozens of times.

MF: I was working when “The Lion King” came out. I remember all the dialogue from that movie. It was on at least three screens and required crowd management. This was before stadium seating, which ended up killing my theater. It finally closed in 1999. We had 15-minute breaks and I would grab some food and sit against the wall in the back of the auditorium because we weren’t allowed to sit in the seats. I watched a lot of movies in quarter-hour chunks. I timed my breaks so I could see new sections of the films each day.

GC: Did your family encourage your interest in moviemaking?

MF: They were supportive of moviemaking as a hobby. They gave us access to the house. My parents appeared in my movies sometimes. They preferred that we were doing that rather than having us out in the world unsupervised. If we were making movies, they knew where we were. One of them even said, “At least you’re not out there drinking and getting high.”

When I said I wanted to make movies for a living, there was some very healthy skepticism of that idea. I received a lot of encouragement to think about doing anything else. I tried to obey by being an education major when I went to college. I planned to teach history. But after my first year, I pivoted once I took an introduction to film class. I knew it was what I really wanted to do. I remember my parents being worried for me.

As a student, I made some Mini-DV features. And I had some great teachers. One of them was Tom Brandau. Tom had just made “Cold Harbor” He was proof positive that one could be a feature filmmaker.

GC: Tom inspired so many students in so many ways.

MF: He had a huge impact on me. I met him in the film department at Towson University. I ended up taking several of his classes, including directing for the camera. Tom was a teacher I admired and respected, but we also became friends very quickly. We would hang out after class sometimes. I would help with his projects. I got to help with post-production on “Cold Harbor” when he was finishing it up. He appeared as an actor in my projects, something he did for many of his students.

Tom was my favorite instructor at Towson and the one I grew closest to, personally. If we had a birthday party, or similar event, Tom was the rare teacher who was welcomed into that circle. We stayed in constant communication after I graduated and moved to Los Angeles. There was, and still is, a network of Brandau alumni in L.A. It is even bigger now than it was when I got here.

Tom was unique among the faculty because he was a feature filmmaker. Tom had a body of work to back up everything that he was teaching us. His practical experience on set was invaluable. You learned from Tom in the classroom but you also learned from Tom in the field. He would be there to support student projects no matter how small. He would show up on a Sunday morning at 5 a.m.

He was a mentor and a friend and a formative part of my life. I miss him a ton. I am so happy to be returning to Fargo but I am so sad he won’t be there.

GC: We have Tom to thank for bringing you and your work to the Fargo Film Festival.

MF: That’s right. “Oculus” back in 2006. And then in 2011, you hosted the world premiere of “Absentia.” Tom always urged me to keep shooting and to do whatever I had to do to make a living out here. Tom celebrated every new job. I can hear him saying, “That is great! That is great! Master that job. Seize the opportunity to learn more.”

Later, when his health was declining, I didn’t always know what was going on with him, which I regret very much. I invited him to visit me on my sets. I gave Tom a tour during “The Haunting of Hill House” shoot. He got to see the Overlook set on “Doctor Sleep.”

GC: I saw some of those photos. He and Janet absolutely loved that.

MF: Generous is the word that describes him. His earnestness as a person also radiates out of his work. He demonstrates the idea that you can feel a filmmaker through the screen. He understood the value of turning that camera in on yourself as much as on the subject of your film, like he did with “Cold Harbor.” He chose not to hide where that story came from and he used the film to process what was going on in his family. And that was inspiring to us.

It is easy in this industry to be discouraged. Too often, people criticize you and try to hold you down, but Tom always lifted you up. He was generous and he was brave and he was gentle, always.

GC: We know how Tom felt about physical media. Are you a collector as well?

MF: Yes. I am a huge supporter of physical media. I still have some LaserDiscs, even though I currently need a working player. Physical media is critical. Critical to the study of cinema and to the survival of cinema. I have worked for the last four years at Netflix, which is kind of the enemy when it comes to physical media. I tried so hard to change the position from inside, to get them to invest in physical media. I wasn’t successful. Now that I am at Amazon, things are different. They are more supportive of physical media.

There are some movies I have bought on every format, including HD DVD. A few titles I feel like I have bought a dozen times, since they are very wise to crank out all the various editions. I have bought “The Evil Dead” trilogy so many times. “Army of Darkness” alone, I have purchased multiple times. There’s another new edition on the way and, well, yeah, I’m going to buy that one, too.

I have several editions of “The Godfather,” “Casablanca,” “Lawrence of Arabia.” And just when I think I have it cracked with these beautiful sets, 4K UHD changes everything again. Back to the drawing board. The Criterion Collection is very important to me, and now their library is starting to get the 4K UHD upgrade. Sometimes without changing the artwork. And I’m buying them again!

Collecting movies is a major priority for me and has been since I started a VHS collection. When I made my own movies on VHS, I spent days hand-drawing and designing the boxes because they weren’t real until they could be on the shelf next to the others in the collection.

GC: Do you archive copies of your own movies?

MF: For my own work, I have sought out every domestic and international release that I am aware of. It is fun to chase them down. The Japanese set for “Doctor Sleep” is my favorite one. Comes with a wonderful booklet that I can’t read, but it looks great.

For the Netflix projects, I have sought out Blu-ray bootlegs. I have “Midnight Mass” and I will do the same for “The Fall of the House of Usher.” The bootleg quality is excellent, by the way. I would be railing against bootlegs under any other circumstances, but for titles that are simply not available, and will never be available on physical media, I am so glad that they exist.

GC: Streaming is slippery. And unpredictable.

MF: When you buy a movie on iTunes, you don’t really own it. There is an illusion of ownership. The idea that at any time a title can be removed from circulation – and we are seeing it happen now to first-run stuff – is awful. It is like titles are being erased. Without physical media, they are just gone. Unfortunately, I believe that is only going to get worse.

I am in a position to speak to many positive and negative things that streaming has done for the business and for storytellers. And I have benefitted from Netflix more than anyone that I am aware of, creatively speaking. But I will always be a little furious that “Midnight Mass” will not be available on Blu-ray. There is no reason it shouldn’t be.

GC: I understand you did your best to convince Netflix to release Blu-rays.

MF: Like Andy Dufresne’s letter writing in “The Shawshank Redemption,” I reached out regularly to Netflix. For the longest time, they ignored me. Finally, we had a conversation and it looked for a second like they might explore it. Once it became clear that I was moving to Amazon, though, that possibility abruptly died.

I will continue to try. I have one more bite of the Netflix apple with “The Fall of the House of Usher.” I am going to start talking to the press about physical media a lot more, too. It is that important to me.

Having learned a lesson, I am now trying to put agreements in place in my deals. I won’t direct unless there is a guarantee for some kind of archival physical release. We’ll see how that goes.

GC: You have also recorded unofficial audio commentaries.

MF: Yes, sometimes during podcasts. I love doing that. I am also grateful that the “Haunting” series was a Paramount co-production, because they maintained the home video rights. That’s why “Hill House” and “Bly” are available on Blu-ray. Although they just wanted to do DVD! I had to arm wrestle them into high definition.

GC: I like the way that you pay homage to favorite films and filmmakers in your work.

MF: I prefer to call it quoting, but we are ripping off all sorts of stuff. Sometimes in the weirdest and unlikeliest places. For example, I tried to recreate the first “Rear Window” kiss between Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly when I was making “Ouija: Origin of Evil.” Right down to the slightly slower speed.

Cinema is a language and the love of cinema is a language. You get to speak that language with your collaborators. I can turn to my DP, who loves movies as much as I do, and instead of offering a technical description, I can say, “Do you remember in ‘Lone Star’ when they do that wonderful hand-off to the flashback with the lighting change?” We use the movies as our primary vocabulary.

I was jamming “Casablanca” into “Doctor Sleep.” I thought, “When am I going to be at Warner again? Let’s do it!” Some of this stuff is homage, but some of it is subconscious. I may look at it and realize, “I thought I was being clever, but actually, I know exactly where I’ve seen that before.“ When you love movies, you celebrate them on both sides of the camera.

GC: “Doctor Sleep” honors both Kubrick and King without any disservice to the other.

MF: That was the goal. I am grateful that is how the movie is perceived by as many people as it is. It is a love letter to both of them, but I have also described it as a parent trap. Trying to get mom and dad to stop fighting.

That movie was so much fun because I got to interrogate the aesthetic choices of Stanley Kubrick in real time, on his sets. I got to see where he put the camera and which lenses he chose. And if I had a question, I could try it over here. And I could try it over there. “Oh, so that’s the amazing thing about this spot! It creates a symmetry that is impossible anywhere else.”

Kubrick knew it and I only found it because I had all his dance moves written down. It was like going to film school again, but in the most surreal way, by walking through a movie you love and interacting with it. Some of the time we were recreating something and other times we were going off on our own.

It was a remarkable challenge and so much fun. We were grinning all day. And frequently saying, “How cool is it that we get to do this?” You’re standing in the shadow of giants. That can be intimidating and you can even feel like you don’t deserve to be there. But they let us do it, so the joke’s on them!

GC: In episodic storytelling, are you making ten feature films or is it one really long movie?

MF: That’s a great question. I asked myself that question and went back and forth. I view them as multi-act movies. The limited series is my favorite format, because you get to do so much with characterization. And the writing challenges are unique. But I view “Hill House” and “Midnight Mass” as long films.

Ongoing series are different. I only tried that once and it is much harder to have arcs that conclude while always making things seem like they are just beginning. It is a weird thing to do. My shot at an ongoing series didn’t work the way the limited series worked. A lot of that was studio interference. “Midnight Club” got beat up extra hard because we got away with so much on “Midnight Mass.” There were a lot of things about that show I knew were problematic – things that Netflix insisted on. And I said as much. But I was overruled.

The pressures are different when you are trying to do something that is ongoing. Things are more hypothetical. In a limited series, you have a beginning-to-end vision and they defer a lot more. With an ongoing series, everything is up for discussion and conversation. Any aspect can change at any time. You can end up reacting to the whims of one or two people. “What if we’re going in the wrong direction?”

From a finished product perspective, the limited series has become my favorite way to tell a story. They are exhausting to make, though. I would prefer to make a theatrical movie because it doesn’t take over your life for nearly as long. My next goal is to get back to movie theaters. I’ve been away since “Doctor Sleep” and I want to get back.

GC: What attracts you to horror?

MF: I think it is interesting that horror is one of the genres that has a strong anti-audience. That group of viewers who are just not interested. It is rare to hear someone say they won’t watch dramas or musicals. Horror can be uncomfortable. Horror promises an emotional experience that isn’t always pleasant.

I think horror is a vital genre. I make horror because when I was a kid, I was terrified of everything. I couldn’t watch scary movies. I was prone to nightmares. I had social anxiety. I was scared of my own shadow. I was a frightened kid.

But what I learned as I began to look into horror movies and horror fiction, when I got through a scary book or chapter or movie, I was that much braver at the end. Braver in tiny increments. I realized that the acquisition of that bravery and that courage was like any exercise you do, any muscle you flex. It spilled over into my real world. It made me better able to cope with stress and anxiety.

As a genre, horror is critically important for us. One of the first emotions we feel as humans is fear. We are scared of the dark. And the genre exists to help us to defeat that fear. And we get to do it in a controlled environment. While we are there, it takes all these things that are the hardest and scariest to look at and creates a safe space to confront the fear inside ourselves.

GC: Horror can be life-affirming.

MF: In my own work, I want there to be empathy and humanism and hope and love and forgiveness in equal measure to the darkness that’s on display. Not all horror movies are like that and I understand that people can be put off. But I encourage them not to dismiss the entire genre.

I only tell the stories I tell because I grew up reading Stephen King. And he has said that there is no horror without love. I think he understands the balance. So that is something I strive to do in everything I make. I don’t think of them as movies or shows about ghosts or vampires or demons, I think of them as stories about people. And ultimately, stories that have something beautiful to say about people. That’s why I love what I do and am never leaving the horror genre.

You hear people say that horror is just a springboard to launch into “real” movies, but I take umbrage at that. I am so lucky to work in the genre. I think it is one of the most important ones that exists. Fans understand it and that’s why they are so passionate. Horror fans are some of the kindest people I have ever met. I’m honored to be in their company.