Movie review by Greg Carlson

Multi-talented visual and performing artist Miranda July delivers an incredibly sure-handed feature film debut with “Me and You and Everyone We Know,” easily one of the year’s most insightful and challenging movies. Having already collected prizes at major film festivals, July’s film is a triumph of ensemble performing, especially noteworthy for the remarkable portrayals offered by young children. “Me and You and Everyone We Know” belongs to that category of offbeat, one-of-a-kind tales that inspire fervent cult followings but little mainstream box office success. Ironically, the hardcore supporters like it this way, as the movie can comfortably remain a secret treasure shared via enthusiastic word of mouth, without the risk of becoming too popular.

Set in the technologically dominated suburban present, “Me and You and Everyone We Know” resembles in many ways the work of Todd Solondz, but bursts with a warmth and humanism often missing from films like “Happiness” and “Storytelling.” While Solondz often highlights the grim and the cynical, July embraces a refreshing hopefulness that only occasionally skirts the edges of too-cute preciousness. Both directors depict frank sexual situations involving children, and both directors are capable of triggering feelings of queasiness as a result of these situations. While “Me and You and Everyone We Know” contains scenes that might unnerve parents of pre-teen and teenage kids, July refuses to judge the actions of her characters, and the result is a scary but bracing look at the ways in which young people navigate the treacherous waters of sexual curiosity and initiation.

Skittish viewers will wince at some of July’s more graphic content, but the director’s range is so far-reaching and original, viewers can readily grasp what July is saying about our inability to find fulfillment and connection with other people. In one jaw-dropping scene, Robby (Brandon Ratcliff) composes a scatological scenario so outrageous it fuels the fantasy of a chat-room correspondent who has no idea that a six-year-old is on the other end of the conversation. Another storyline details the dangerous flirtation between two young girls and an older man. “Me and You and Everyone We Know” is not reducible to its preoccupation with sex, however, and its central storyline plays with the conventions of the traditional romantic comedy.

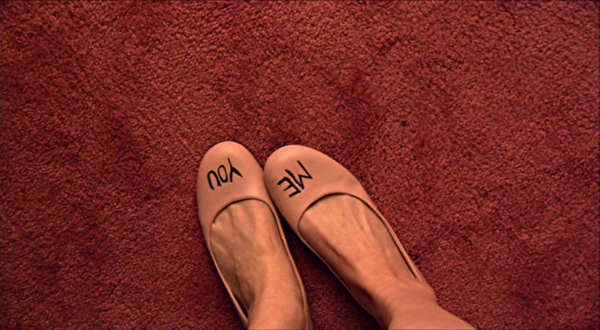

Writer-director July plays Christine, a struggling artist who pays the rent by chauffeuring elderly passengers on daily errands. Christine’s path intersects with Richard (a superb John Hawkes), a terrified shoe salesman dealing with a painful separation from the mother of his two boys. Both characters suffer from indignities both tiny and substantial, and July and Hawkes manage to convey complex interiority in a compelling and utterly believable manner. What makes “Me and You and Everyone We Know” work so well is July’s willingness to show Christine and Richard as imperfect, and their limitations and weaknesses – Christine’s passive-aggressive desperation and Richard’s irresponsible self-abuse both physical and psychological – forge their personalities into recognizable images of ourselves.

Along with July and Hawkes, the rest of the actors make memorable impressions. Ratcliff and Miles Thompson, as Richard’s sons, demonstrate the heartbreaking confusion resulting from parental break-up. Carlie Westerman, as an obsessive collector of home appliances, employs her hobby as a bulwark against potential pain, and her meticulously appointed hope chest reminds us of her own deepest worries and anxieties. “Me and You and Everyone We Know” is filled with wondrous moments, though some will likely find the relentless self-documentation overpoweringly syrupy. Others will respond to the film’s dogged determination and its indomitable spiritedness. Either way, “Me and You and Everyone We Know” is not easy to forget.