Movie review by Greg Carlson

Sean Penn delivers the finest and most satisfying of his quartet of features with an adaptation of John Krakauer’s “Into the Wild,” the tale of a privileged young man who perished while camping alone in Alaska in 1992. Penn also adapted the text of the bestseller, and his screenplay effectively translates the book into cinema, leaving out passages that might have led viewers to embrace a simple explanation for the fierce idealism that sealed the protagonist’s fate. Instead, the director conjures up a heady, and oftentimes mystical, reflection on core themes that have interested headstrong young people throughout the ages.

Christopher McCandless, who often exchanged his given name for the roadworthy moniker Alexander Supertramp, captured the attention of millions when the details of his fatal odyssey were chronicled by adventure writers like Krakauer, who turned his original article for “Outside” magazine into a tremendously popular book. Krakauer might have speculated and theorized beyond the limits of caution, and Penn certainly does the same, but the story of McCandless continues to engage initiates for myriad reasons. Surely, had McCandless not kept a journal detailing his final days, nor taken several rolls of film, there would not have been enough fuel to fire the imagination or flesh out a portrait.

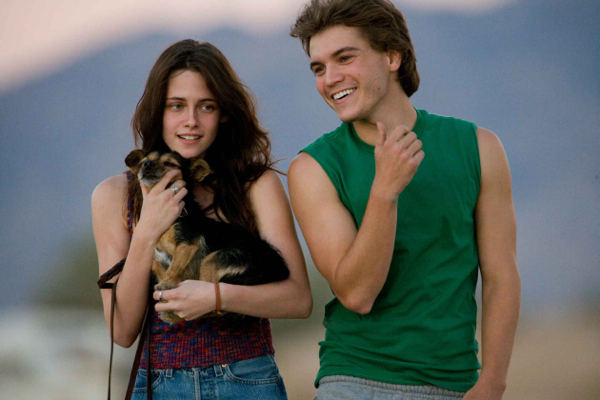

Because the vagabond articulated his convictions, sometimes in the margins of the copies of “Walden,” “Doctor Zhivago” and “Education of a Wandering Man” that were found with his remains, readers identified with McCandless. His admirers and detractors, not a few of whom hail from the forty-ninth state, continue to argue about him. Emile Hirsch, the actor who portrays McCandless, gives a performance that is rich in suggestion regarding McCandless’ personality and harrowing in its physical transformation. Hirsch’s is a performance that in its seriousness and conviction echoes some of the memorable work Penn has done in front of the camera.

Penn’s canniest choice in the movie version of “Into the Wild” is to flesh out the various characters McCandless met on the road. Krakauer did the original detective work, tracking down many of the people whose fleeting interactions with McCandless would later resonate when he was no more. As family and friends of McCandless, Marcia Gay Harden, William Hurt, Jena Malone, Vince Vaughn, Catherine Keener, and Brian Dierker all invest themselves in their roles. It is Hal Holbrook, however, as an elderly widower who forges a special kinship with McCandless, who radiates the warmth that gives the movie its beating heart.

“Into the Wild” resists the temptation to beatify McCandless as a visionary who perished in pursuit of the great truth. The contradictory nature of his brief life is fully explored, and we are allowed time to contemplate the apparent foolhardiness of walking into the wilderness without having taken the necessary precautions against peril and harm. In “Into the Wild,” Krakauer argues that to criticize McCandless for failing to do his homework utterly misses the point, and that McCandless knew the great risk he was taking when he trekked beyond the marked path. Penn takes heed of this, and as a result, “Into the Wild” should be seen by everyone who seeks to understand the inexplicably intoxicating appeal of treacherous, high-risk adventure.