Interview by Greg Carlson

Filmmaker Henry Ferrini discussed “Polis Is This: Charles Olson and the Persistence of Place,” a fascinating portrait of the late poet that will air locally on Prairie Public Television as part of National Poetry Month.

Greg Carlson: Thank you for taking some time to share with us.

Henry Ferrini: First, on behalf of Ken and myself, we want to express to the people of Fargo our concerns and our hopes that the recent floodwaters will quickly subside along with the harms they’ve caused. But we know it doesn’t work that way. We know from being here in Gloucester that these devastations hang around for a while.

But we also know that there’s a spirit in people (one that comes out every so often) and we know that the spirit of good will and good deeds will stick around Fargo long after the water returns to its proper place.

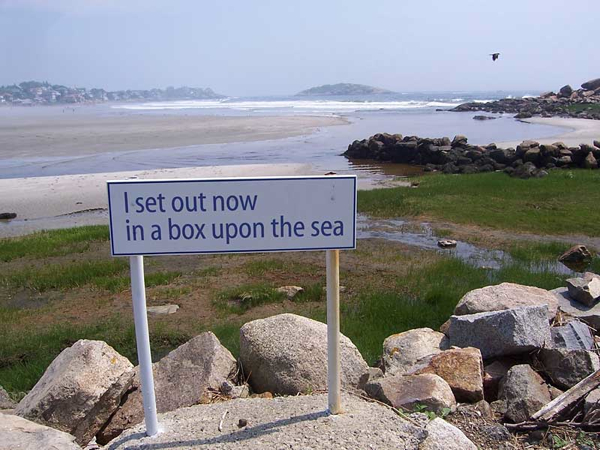

We also hope that the film, which deals expressly with the importance of place, will help soothe folks at this time and give them the encouragement to rebuild better than before.

GC: How did your collaboration with writer Ken Riaf work? Was there a completed script first or did the project evolve as it was being shot and edited?

HF: The film was built from the inside out. We had a framework. We knew that the audience for the film was the person who never heard of Charles Olson and maybe never even read much poetry. With that in mind we set out to tell a story about a man and the place he lives and why that man and his ideas are important today.

Ken and I have worked together before so we know that our styles are very different and that we need to constantly reconcile our viewpoints. Neither of us likes to compromise so we’ve had some heated discussions about content that go on and on like a running gun battle.

But we also see eye to eye on lots of things and we’ve got a lot of trust going and a similar workmanlike approach that recognizes the need to press hard for extended periods with no hope of reward. We’ve each brought different elements to the film, different topics and different people to the screen.

We work well as a team. What we usually agree on winds up being things that make the film better, more understandable. Our challenge is always to avoid explaining things and instead let things explain themselves.

The best I can describe the process is that it resembles the principles in the film that “form is never more than an extension of content.” Do we have a form? Yes, but it’s elastic. Do we have content? Yes, but that’s also elastic. Do we know where we’re going? Yes, but we’re willing to take side trips and detours and to follow unmarked roads and plumb uncharted waters.

We find out what the film is about in the making of it. It tells us, we tell each other, we listen and we argue. The film is the product of that tension, our differences of opinion, uncertainty, a flexible plan and most importantly, an openness to change that allows the content to unfold itself and reveal its form to us.

GC: Can you talk a little bit about how you approach the visual design of your movies? How did you decide what kinds of images would be paired with the various poems?

HF: I had a great advantage in that I live on the set. When “The Perfect Storm” came to Gloucester, I was out shooting as much as possible and being told by security to get off the set. I’d just return the volley and say, “You are the interlopers on my set, don’t think you can kick me out. I’ve been documenting this town for 20 years.”

Warner Brothers came and went and I remained shooting every time there was amazing light or when the atmospheric conditions made for magic. That’s why painters like Stuart Davis, Marsden Hartley and Winslow Homer came to Gloucester – there is a quality of light that is powerful.

“Song Three” is an example of how things evolve. When we were going through all the stock footage, much had been shot in winter. We then came across a recording of Olson reading the poem. The tone and quality of the footage matched the tone of the poem. We where able to cobble it into a sequence that spoke volumes about Olson’s attitude regarding materialism, while exploring his hermitage.

GC: “Polis Is This” does not follow the conventional patterns of a biographical documentary, employing instead a lyrical, impressionistic approach that allows for greater exploration of the subject’s philosophies, thoughts, and ideas. How difficult was it for you to find a balance between conveying the historical information about Olson’s life that curious audience members might want to know versus sharing the poet’s writings and feelings?

HF: The answer is that we did not want to make a biography, or a chronology like this happened, then this happened, then this happened. If you’re curious about Olson’s personal life you’ll go find out for yourself. By the way, that’s what Olson prescribes for the curious: go find out for yourself.

It’s easy to go off task and we wanted to get to the poetry part of it. Olson’s son Charlie, a carpenter, will tell you in construction, “If you want to get something, you have to give something up.” It means if you want that closet in the room you have to give up some floor space. It’s physics; no way around it.

We wanted the floor space for the poetry and commentary, so no closet and the clothes of Olson’s life are folded in the corner on the floor if you want to look.

We gave up some of the personal for more of the poetic. It was a difficult and constantly shifting balancing act. You really can’t have it both ways, so we went with the work and used shorthand to inform viewers about his personal life. For example, we learn through his writings that his father was a letter carrier and shortly after that Olson’s son Charlie tells us about his dad’s upbringing. By that point we know Olson’s father, his son and the outline of his youth.

GC: Along with several literary notables, we get to see and hear from Charles Peter Olson, the son of Charles Olson, several times during the movie. How involved was he during the production?

HF: It’s a fair question with a complicated answer that can’t be spun out here. But it’s sufficient to say that Charles Peter Olson is a remarkable individual who for sound personal reasons was very reluctant to engage with the film. Over time he overcame that reluctance but it nearly cost Ken, myself and Charlie our mutual and interlocking friendships.

Gloucester is a small town, especially in the winter, and it’s very scary when one’s work spills over into one’s personal life and threatens harm to an intricate network of relationships. Charlie’s cooperation was vital, essential really, and hard to come by. His perspectives give new insights into understanding his father’s work that aid students and scholars in their interpretive pursuits.

GC: Since you never had the chance to meet Olson, tell me how the archival footage of him affected you during your process.

HF: Olson’s personality comes straight through, as does the force of his intellect. It is powerful to watch on film and it must have been very powerful in person. I believe Olson could stand toe to toe with the best minds of any time.

We looked at hours of Olson outtakes from the American Poetry Archive at San Francisco State College. These were Olson’s “home movies.” They were taken at 28 Fort Square, the poet’s home from 1957 until his death in 1970. Seeing the rooms, his books, art, views from his windows overlooking the harbor, even the door jambs that were covered with writing gave us an intimate look at the man.

GC: There are several fascinating concerns of Olson’s explored in the movie, from the observational powers of letter carriers to the devastation wrought by urban renewal. What thread interested you the most?

HF: The common thread is that there is no common thread. All are different, and all lead in divergent directions that have their own destinations.

For Ken I think it was that the local and the universal are the same things known by different names and that in one drop of seawater a person can know the entire ocean. For me it is similar. We all experience reality through the lens of the local, whether it is in Fargo, ND or Gloucester, MA.

Olson calls place “the geography of our being.” It’s a map of our lives. To understand where we have been and where we are going we need the map. It provides us a way of knowing the world around us. Each of us has our own map that comes from our people and the place we live. We are in charge of the investigation. As Olson said, “You’ve got your own track, your own train, you can go anywhere.”

GC: Both you and Charles Olson are identified closely with Gloucester, Massachusetts. How did the citizens there respond to the movie?

HF: As far as people in the street who talked to me, well they’re the backbone and glue of the film they are the living polis, they are the poem. And so the film would not be what it is without them. The UPS driver, the fisherman, the painter, the artist, the barber, the waitress reciting Emily Dickinson… I mean really, what a cast.

Folks in Gloucester are the finest kind of people and this is still a working place, a place to go fishing from, and for those who were interested in the film, most folks liked it. But most folks are pretty absorbed in their daily doings.

They don’t always have the time to look up from the immediate things that press them for time. So I’d say the film was well received by those who received it and went unnoticed by most everybody else.

GC: What projects are you working on now?

HF: I am developing a film about the great tenor saxophonist Lester Young. It is based on an audio interview that was done in a Paris hotel a few months before Lester died. The film is located in Paris, New York and New Orleans.

I hope to use the interview as the spine of the film and wrap other stories around that core. I’m planning an upcoming interview with Sonny Rollins, who played with Prez in Detroit.

“Polis Is This: Charles Olson and the Persistence of Place” will be shown on Prairie Public Television on Thursday, April 2 at 8pm and Saturday, April 4 at 2am.