Movie review by Greg Carlson

Tim Jenison, an inventor whose work in video editing solutions and computer graphics has made him a wealthy man, embarks on an odyssey to “paint a Vermeer” using an optical device Jenison believes might have been similar to something theoretically available to the Dutch master. The result of Jenison’s obsessive quest is less interesting than the lengths to which he goes in the process. “Tim’s Vermeer,” the story of Jenison’s grand experiment, is captured by magic/comedy tricksters and skeptics Penn and Teller. Penn Jillette provides on-camera commentary while silent partner Teller makes his feature debut as director. Appreciators of great painting might take issue with the suggestion that Vermeer “cheated,” but the film does raise some thought-provoking ideas concerning the intersection between art and technology.

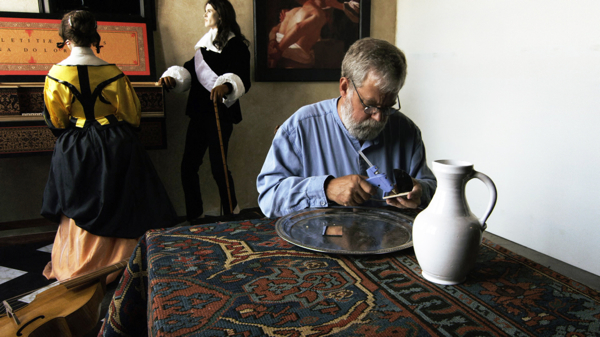

One of the movie’s most vocal critics is Jonathan Jones, who wrote about “Tim’s Vermeer” in “The Guardian.” Jones took the position that Teller had made “an art film for philistines,” and suggested that, ironically, the “failure of Jenison’s device to create any of the power of a real painting by Vermeer puts all these theories about painting and the camera obscura and ‘secret knowledge’ in their place.” Reading the commentary of Jones causes one to speculate that the documentary might have been richer had some respectable voices of dissent been allowed a measure of screen time. Instead, Teller trains his camera firmly on the progress of Jenison as a lavish recreation of the objects and elements depicted in Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” (or “Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman”) is assembled.

The strongest point made by Jones reminds us that the movie never presents images of the Vermeer original, but instead relies on inherently inferior and misleading reproductions of “The Music Lesson.” A short section of the movie is devoted to the unsuccessful efforts of the filmmakers to photograph the painting, which is held privately in London by the British royal family. Jenison is ultimately granted a short personal audience with the piece, but viewers are asked, somewhat anticlimactically, to accept his breathless descriptions.

Many viewers will find it entirely possible that critics like Jones overstate the case against Jenison. “Tim’s Vermeer” is devoted to technological possibility at the expense of deeper conversation and contemplation of the “mystery of history” presented by Vermeer’s uncanny and unfathomable talent. Undoubtedly, even if Teller had devoted equal time to explorations of Vermeer by the artist’s greatest scholars, the central premise of Jenison’s experiment would have most likely remained the same.

Teller includes the testimony of British artist David Hockney, whose 2001 book “Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Techniques of the Old Masters” suggested that the use of camera obscura and optical assist techniques advanced photorealism in painting. Philip Steadman, another supporter of the optical assist theories, also appears in “Tim’s Vermeer.” Steadman’s “Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth Behind the Masterpieces” was published the same year as Hockney’s “Secret Knowledge.” The principal argument opposing Jenison, Hockney, and Steadman raises the “so what?” question and makes the emphatic claim that Vermeer’s genius resides not in the possibility that some kind of mirror allowed him to “copy” reality but rather in the authenticity and singularity of his transcendent vision.