Movie review by Greg Carlson

Self-conscious, geeky coder Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) wins a contest to visit the sprawling private compound of his boss Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), a computer genius using his billions to pursue artificial intelligence in the form of an erotically charged machine named Ava (Alicia Vikander). Screenwriter/novelist Alex Garland makes his directorial debut with “Ex Machina,” the alternately intriguing and infuriating result of Nathan’s scheme to use Caleb as human bait in a twisted version of the Turing Test. “Ex Machina” is pretty shaky as far as anything resembling an earnest exploration of the philosophy of AI goes, but as heterosexual male fantasy, it’s what Bryant in “Blade Runner” would call a “basic pleasure model.”

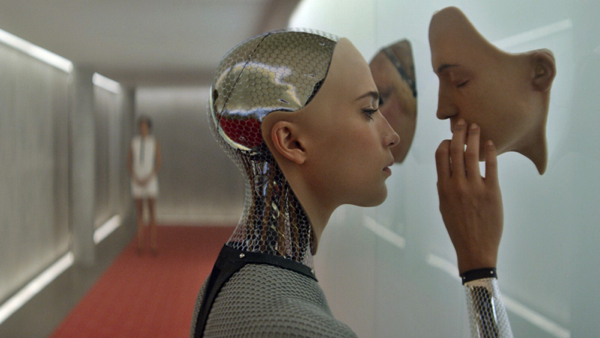

It doesn’t take more than a minute to figure out that Nathan is not to be trusted, and despite the ostentatiousness of his modernist keep, complete with elaborate key card security system and an original Jackson Pollock painting, the bachelor pad/research facility is strangely susceptible to power outages that shut down the audio and video surveillance that Nathan uses to monitor the meetings between Caleb and Ava. While theoretically, Nathan’s invention could have taken any form, its manifestation as a kind of motorized Aphrodite requires Garland to confront the competing impulses of lust and intellect. Like Jason Lee’s lonely tech mogul discovers in the largely forgotten “Mumford,” money can’t but love, but it can pay for, as Stephen Holden noted, “a line of robotic sex surrogates that are virtually indistinguishable from flesh-and-blood humans.”

In one sequence, previous iterations of Nathan’s full body experiments are revealed like a perverse, Frankenstein-ian cross between Bluebeard’s wives and next gen RealDolls. David Edelstein identifies the plot’s indebtedness to classic crime ménage a trois, writing that the movie has “everything to do with James M. Cain and the noir-ish world of abusive husband-masters, wily female slaves, and poor-sap male ingénues.” An emergent femme fatale, Ava perfectly exudes a Marilyn Monroe-like combination of childlike vulnerability and potential sexual availability certain to cause trouble for anyone foolish enough to offer protection or rescue.

After Vikander, the most entertaining thing about “Ex Machina” is the bugged-out comic presence of Oscar Isaac, who more often than not gives the distinct impression that he recognizes the ridiculousness of the movie’s “deep” thoughts and is just having a blast winking at the audience. His Nathan is bright, petulant, aggressive, grating, and confident to the extent you can see him compensating for a fragile insecurity with every backslap and faux sincere use of “bro.” The fantastic, synchronized disco routine by Isaac and Sonoya Mizuno set to Oliver Cheatham’s “Get Down Saturday Night” is solid gold.

Tasha Robinson identifies the “unmistakable masculine collusion between [Caleb] and Nathan over [Ava], as if Nathan were pimping her out,” and Garland stays firmly and purposefully in the orbit of the boys. Garland’s move might deliberately occlude Ava’s intentions until late in the game, but it also keeps her at a distance that puts a huge strain on the film, since she is by far the most interesting character and her absences are always keenly felt. In this sense, “Ex Machina” is a far cry from Spike Jonze’s “Her” and Jonathan Glazer’s “Under the Skin,” two superior examples of science fiction that better understand – and are unafraid to engage with – nuances within the politics of gender.