Interview by Greg Carlson

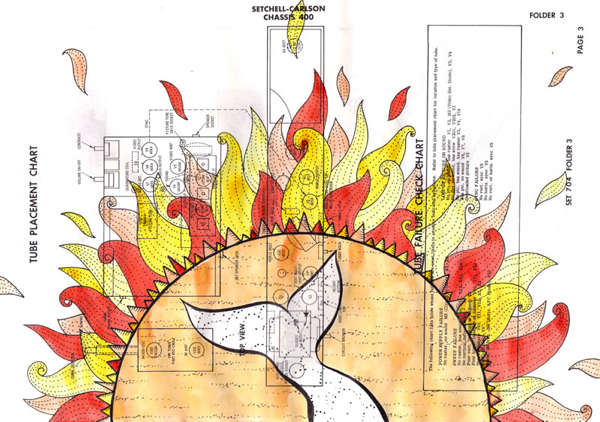

Ohio-based artist Matt Kish, who spent roughly 18 months illustrating “Moby-Dick” with a drawing for every page of the Signet Classics edition, has seen the fruits of his labor published as a beautiful, full color volume from Tin House Books.

Kish will present a talk on Thursday, January 19 at 7:30pm in Jones 212 (Fugelstad Auditorium) on the campus of Concordia College.

The event is free and the community is invited to attend. Copies of “Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page” will be available for sale and signing following the presentation.

The High Plains Reader’s Greg Carlson talked to Matt Kish about the Great White Whale.

Greg Carlson: You name “Moby-Dick” as the galvanizing book of your life. Can you describe when and how you first became aware of “Moby-Dick” and its power?

Matt Kish: Interestingly enough, especially in these times when children and younger adults are so often roundly criticized for their immersion in movies, television, videogames and the internet, my first experience with Moby-Dick was seeing the 1950s film version, the one starring Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab. I was quite young, perhaps 5 or 6 years old, and I was at my grandmother’s house for my annual Saturday visit.

On WUAB TV in Cleveland, Ohio, Superhost would show Godzilla movies on Saturday afternoons and for some reason on this day I kept watching even after the credits rolled. The next movie up was Moby-Dick and I remember being very bored at first. Too many boring, normal historical details. Sailing ships. People in funny clothes. All of that.

But eventually I saw this vast, white whale on the screen and I have vivid memories of its bulk rolling through the waves and an eye staring balefully out of the TV. I was smitten. Here was a monster which was almost real! Maybe could be real! That drew me to the screen and I watched right through to the climax breathlessly.

I must have talked about that movie incessantly because in a very short time, some family member gave me a tiny, square, heavily abridged 200 page children’s version of the book. What I loved so much about this version was that every other page had a scratchy black and white ink illustration. Some of the terrified me!

But here was the entire story, and now I could revisit it any time I wished. What I keep coming back to as I think about this project of mine is how from the very beginning, the story of Moby-Dick existed for me as a primarily visual narrative. First as a film, next as a heavily illustrated book. Those images have never left my mind, and the story has never seemed, to me at least, to be just words on paper.

GC: How many different editions of the novel have do you have in your collection? Is there one that “rises above” the others?

MK: For a time, I was slowly building a collection of different versions based primarily on my love for the book and my mentality as a long-time comic book collector. Prior to this project, my favorites were the Arion Press edition illustrated by the great Barry Moser and set in a newly created font, called appropriately enough, Leviathan.

This appealed to me almost as a fetish object since in some ways the entire project was so over-designed and attention had been lavished on things which were absolutely unnecessary but delightful to a an obsessed book collector like me. Another favorite was the Classics Illustrated comic version, but not the old one.

The one I liked was a newer version, from the 1990s, illustrated by Bill Sienkewicz. His take on the imagery from the book was so brutal, so bloody, so surreal. I came across it as an undergrad and, other than its short comic book length, it seemed the definitive version of the story to me.

My many other versions all tended to be illustrated to some degree, but none of them were especially noteworthy, valuable or expensive. Since completing my own project though, I came to feel like I had been so deeply immersed in the novel for so long and in such an intense, visceral way that I needed a kind of catharsis.

I held on to that Sienkewicz version and the tattered Signet Classics paperback edition that had been my guide through my own illustration project, but the rest I gave to friends or donated to libraries. It was time for me to give myself some room, some space to breathe, and even though I know I will read the novel again and again and again, it will be some time before I make that plunge back in.

GC: You elected not to pursue formal training as an artist, but you have been creating art since childhood. What were some of your favorite classes in high school and beyond?

MK: It’s funny, I’m not sure I ever made a specific choice not to pursue training or an education as an artist, it simply never occurred to me that it was an option. I had wonderful parents who would have supported any career I wanted to pursue, so it’s not like they held me back.

As a kid, and even as a high school student in the 1980s, I just felt like drawing was as much fun as eating candy or playing videogames, and you couldn’t get a job doing either of those other two so I just somehow figured that going to college for art wasn’t even really possible. It may, however, come as no surprise that throughout junior high, high school, and college, my favorite classes were always the literature classes.

I was, and remain, a voracious reader, so being able to read dozens and dozens of books and stories, talk about them in classes, write responses to them and dig deeper into them was heavenly for me. Perhaps my favorite class was as a junior in high school, a class simply called “Novel” or something like that, where we spent an enormous amount of time exploring in great depth the novels The Great Gatsby, A Farewell to Arms, Wuthering Heights and The Fellowship of the Ring.

What was remarkable about that class was not the books themselves since most high school juniors and seniors would have read them by that time. It was how deeply we were able to explore each novel and the environment which produced each one. At one point I remember the class scrutinizing a facsimile of the galley copy of The Great Gatsby and discussing the nature of publishing in the 1930s. Needless to say, my great love of literature was fixed in me from a very early time.

GC: You have described your creative process in terms of making art as “analog,” but word of the project really took off and spread through the use of technologies available on the web. As a person with a hand in each of these worlds, do you ever think about how the old and the new intersect for you?

MK: I don’t think about that intersection often, and when I do it’s not a comfortable fit for me. I have a lot of reservations about what I see online, and the way that some seem to relentlessly flog what’s really some empty content. Social media, blogs, and the internet in general have so much potential, but most people’s use of those things is just incredibly lazy.

Blog posts shrink and shrink until Twitter, or micro-blogging, rules the day. How can you really say anything that matters in 140 characters? I have a special rancor for Tumblr which many seem to use to offer contextless collections of images that they themselves had no role in the creation of and are not willing to make any intelligent statements about.

All too often, a Tumblr exists as an excuse for someone to find a lot of things, “curate” some collection of these things, and offer them up as evidence of either how hip they are or how they can find things online that no one has ever heard of. It sickens me. With my own blog, with all of my own online efforts, I try to mirror who I am in reality.

In other words, I hope that if someone were to read one of the posts on my blog they would get at least a sense of who I am as a person and what matters to me. I know there are a lot of people that do this as well, they just seem to be a tiny minority drowning in a sea of internet noise.

GC: Did you have a favorite character and passage from “Moby-Dick” prior to embarking on your endeavor? Did that shift during or after you completed the work?

MK: In terms of characters, my favorite is and always has been Queequeg. To me, he’s always seemed to be the ideal human being. Far from perfect, certainly, and much is made of his cannibal nature. But he is the epitome of all that is best in us, all that we can hope to be. He is a ray of light and a constant beacon of hope and humanity. For Ishmael, for the crew, and most importantly for the reader.

The first illustration I created for Queequeg came after days and days of trepidation and stress. I knew I had to get it just right. It had to be the perfect visual signifier for this character that meant so much to me. I had seen so many different depictions of Queequeg, with his tattoos and his topknot, and many of them were very realistic.

I knew I wanted to avoid that route since it would be difficult to duplicate time after time and, honestly, it bored me a little. That line of thinking led me to the idea of distilling his tattooed face down to it’s very essence. Patterns on a mask. Nothing more. So my Queequeg evolved into a blue cipher, patterned all over with a beautiful, organic scalloping.

I could draw him over and over and over, and looked for every opportunity to do so. Drawing Queequeg always brought me happiness.

As for favorite passages, there were so very many I was looking forward to. Oddly enough, the passages and quotes that were the most well-known – the “From hell’s heart I stab at thee!” and things like that – made me the most nervous. I knew that those passages, the ones that even non-readers of Moby-Dick were familiar with, carried with them the weight of great expectations.

I worried that viewers would come to those illustrations with something pre-conceived, and perhaps be disappointed or even angry in my own depiction. That was a difficult battle to fight because in spite of those expectations, I simply couldn’t ignore those passages or choose to illustrate something else. My project wouldn’t be complete.

I had to really turn inward, really shut out the world, really zero in on the version of Moby-Dick that had always existed in my own mind and charge ahead with no regard for what anyone else might thing. Fortunately, in the end, I am very proud of every one of the illustrations and believe that they are all true to my own vision.

GC: How did the other harpooneers evolve during the project?

MK: Queequeg, and all the harpooneers really, to me had to be very different from the machine-like, ship-like sailors. These men, these harpooneers, were living weapons. Extensions of the violent greed of the captains and mates that commanded them. Yet they could not be machines, they could not look like machines, because they had to embody that fluid, dynamic killer instinct.

These were the only characters that I spent even a bit of time sketching out before I drew them. I wanted each one, Queequeg and Tashtego and Daggoo, to be utterly distinct from the other. I also considered how, within the novel, each is a rather heavy symbol for their own race, culture or ethnicity. I wanted to address that, but more indirectly.

Looking back, I realize that my depiction of each of the harpooneers is a bit heavy-handed, but my symbolism has always been painted with broad strokes and I don’t regret that. So Queequeg grew from his tattoos and my perception of him as the ideal man, Tashtego drew heavily from totem symbols and Native American ideas, and Daggoo represented an image of pure and intimidating physical might.

GC: Did Melville or Ahab or the Whale or other elements ever visit your dreams during the project?

MK: Ahab, the Whale, Queequeg, Fedallah, the project itself, the idea of the project…all these things consumed me more and more the deeper I sank into it. Slowly, over the 18 months that I worked, it became in every sense of the word an obsession. I don’t think anyone that reads the book, that truly reads the book the way it demands to be read, can escape that.

For me, reading and re-reading pages and chapters every single day, creating an illustration drawn from the book every single day…as cliche as this may sound, it stopped being a book. It stopped being a story. It became first a part of my life, and then my life itself. I truly felt as if I were living the story and walking those salt-stained boards with Ishmael and Ahab and the rest of the crew.

As the end neared, the desire…actually the need to complete this thing, to kill it the way that Ahab wanted to murder the Whale, became almost overwhelming. I began to see everything else that filled my life – my job, time spent with friends, the demands of a marriage – as hindrances preventing from working on the great task I had set for myself.

The whales which had first enchanted and later haunted my dreams began to fill my waking hours as well. I stopped short of hallucinating, but it was impossible for me to not see evidence of the White Whale everywhere I looked. It was all I could think of and at times I could feel my vision dimming as my eyes seemed to turn inward and consider the next illustration as it played out in the theater of my mind.

GC: What does your wife think about “Moby-Dick”?

MK: She is a brilliant person and as voracious a reader as myself, but amazingly she had never read the novel until shortly after I completed my project. At first she said that after seeing the dark places that the project took me to she didn’t want to even think about it but over time, she told me she felt she had to read it in order to understand what had happened.

Not just in the book, but to me. Interestingly enough, her first reading was accompanied by my own illustrations since she said that as she read, she frequently visited the blog to see how I had depicted certain scenes or characters. So in some ways, her vision of the novel is patterned to a great degree after my own. That is a great honor for me.

She talked to me less and less about the book as she neared the end though. I think the journey was taking the same toll on her that it had on me. Finally, after finishing, all she could say, and all she has said since, is this: “It’s a horrible horrible book but a brilliant one. I’m glad I read it and I never want to read it again.”