Movie review by Greg Carlson

Photography buffs and silent film aficionados will enjoy Marc Shaffer’s feature documentary “Exposing Muybridge,” a visually engaging account of curious cinematic forefather Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge’s place as a film pioneer was ultimately secured via the influential motion studies he produced following his ill-fated collaboration with railroad baron Leland Stanford in the early 1870s, but Shaffer attempts to put his subject’s entire creative life in context. Drawing from a series of new interviews with historians, theorists, photographers, and (in actor Gary Oldman) an enthusiastic collector, Shaffer recounts the dizzying highs and abject lows of Muybridge’s fascinating career.

Film students young and old will certainly recall class viewings of any number of Muybridge’s photo sequences come to life through animation, but so iconic are these images, Shaffer ends his film with a montage of allusions in paintings by Francis Bacon and David Hockney, Seth Shipman’s DNA data storage experiments, the photography of William Wegman and Sol LeWitt, and even U2’s “Lemon” and the animated series “Rick and Morty.” Had Shaffer been in production a little later, he could have added Jordan Peele’s “Nope” to the above list. At just under 90 minutes, the film doesn’t wear out its welcome, but there are a few aspects of Muybridge’s colorful legacy that could have used more detail and consideration.

Given that Muybridge’s life spanned 1830 to 1904 – a period, as the movie points out, of remarkable mechanization and modernization – it is a rather tall task for Shaffer to go into as much depth as Rebecca Solnit’s essential 2003 book “River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West.” The talking heads interviewed by Shaffer, including Oscar-winner Oldman, are erudite, charming, knowledgeable, and passionate, but it is a real shame that Solnit is not among them. Her exceptional work, a must-read companion to Shaffer’s documentary, synthesizes several themes alluded to in the film.

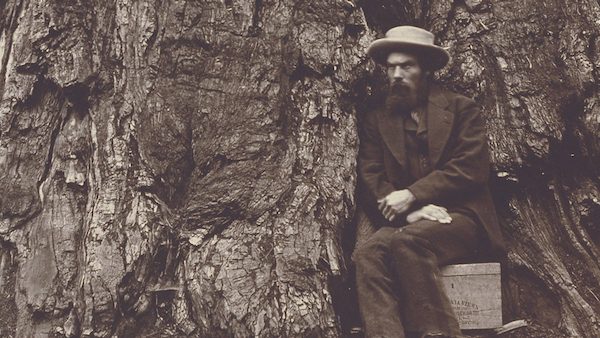

That’s not to say that Shaffer doesn’t acknowledge the most remarkable milestones that link Muybridge to evolutions in image-making. One of the most enjoyable parts of the movie sees photographers Byron Wolfe and Mark Klett lining up near the exact spot where Muybridge took a breathtaking landscape plate in Yosemite National Park. By walking in Muybridge’s footsteps, minus his most reckless and perilous risk-taking, Wolfe and Klett link past and present with spine-tingling immediacy. The ways in which Muybridge edited and retouched pictures by adding dramatic details such as the favored cloud he placed in multiple compositions anticipated cinema’s commonplace manipulation of “reality” in favor of fantasy.

Shaffer frequently returns to Muybridge’s sketchy, dangerous personal character (or lack thereof). In 1874, Muybridge murdered Harry Larkyns, the lover of his spouse Flora, reportedly saying “I have a message for you from my wife” as he pulled the trigger. Over the decades Muybridge scholars have speculated that his utter lack of inhibition could be traced to a serious head injury suffered in an 1860 stagecoach crash. The personal and the professional are often interlaced, and Shaffer’s interview subjects go on to assertively debunk the “science” claims that Muybridge used to legitimize the costly University of Pennsylvania project that would, more than his majestic vistas, his San Francisco panorama, his volumes of stereograph cards, and his zoöpraxiscope, cement his place in history alongside proof that at a gallop, a horse does indeed lift all four hooves off the ground at the same time.