Movie review by Greg Carlson

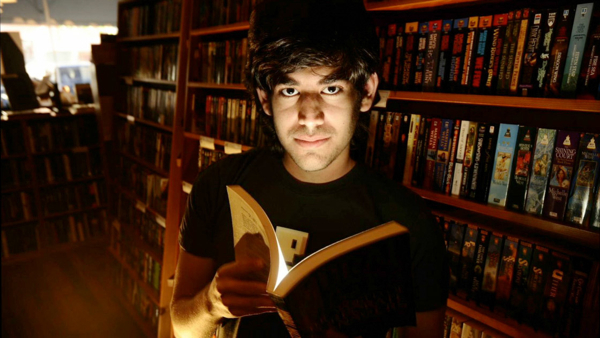

In his sharp biography “The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz,” filmmaker Brian Knappenberger spends very little time on the heartbreaking January 11, 2013 suicide of the title figure. Even so, the death, at age 26, of the brilliant Swartz looms over the contents of the movie, informing and shaping every element of a story that is as much about the future of the Internet as it is about a genius thinker, programmer, and activist who chose to use his mind for what he saw as the common good even when that position clashed with the views of the Department of Justice, inviting the draconian prosecutorial overreach of the United States government.

Knappenberger, whose previous movie “We Are Legion: The Story of the Hacktivists” covered the controversial actions of the international network of digital disruptors known as Anonymous, demonstrates a deep knowledge of cyberculture. “The Internet’s Own Boy” is unabashed, call-to-arms, social action cinema, but the position carved out by Knappenberger and the movie’s impressive list of digital warriors is so articulately rendered that one can envision the previously unindoctrinated being convinced to rethink antiquated and inadequate regulations in much the same way that Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s “Blackfish” turned opinion on SeaWorld.

Swartz was an itinerant and restless participant in much of the contemporary computing landscape he so often helped to create, refine, or improve, and Knappenberger attests to the young man’s iconoclasm as one of Swartz’s most fiercely defined personality traits. From dissatisfaction with the intellectual straitjacket of traditional classrooms to the soul-crushing expectations of showing up to work in an office, Swartz’s refusal to conform to the rules in a rarefied world where those rules are comparatively liberal marked him as a radical among radicals.

Even with an avalanche of complex details to sift, Knappenberger clearly lays out the timeline of events that led to Swartz being indicted for multiple violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. While a research fellow at Harvard, Swartz downloaded some 4.8 million academic journal articles through the JSTOR database, collecting many of the documents through a network-connected switch to his Acer laptop, which he hooked up in a wiring closet at MIT’s Building 16. Aware of the high-volume transfer, investigators collected hidden camera footage of Swartz accessing the small room.

For many reasons, those grainy images captured by the surveillance camera stick with you. At first, it just doesn’t seem like there is much to it. Swartz enters the space with backpack and bicycle helmet, crouching out of frame for several minutes while he hooks up a hard drive and checks on the progress of his download. But the existence of the video – and knowing everything that would happen later – colors the perception of the viewer. Kevin Poulsen wrote, “…It’s easy to see what MIT and the Secret Service presumably saw – a furtive hacker going someplace he shouldn’t go, doing something he shouldn’t do.” Looking back, it is not clear whether Swartz was actually breaking the law, even if he appeared to flout the rules.

With access to Swartz’s family, partners Quinn Norton and Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, and big dogs like Tim Berners-Lee, Cory Doctorow, Gabriella Coleman, and Swartz’s mentor Lawrence Lessig, Knappenberger interviews plenty of voices more than capable of expressing the scope of harm that has been done by public agencies that treat so-called hackers like terrorists. The movie has plenty of indignation and frustration, all of it amplified by the urgency and passion of Swartz’s campaigns. “The Internet’s Own Boy” labors to end with a positive outlook on the 2013 measure known as “Aaron’s Law,” a piece of proposed legislation that has made virtually no progress in a system hell bent on a strangled public domain, unfailing and Orwellian support of a greedy corporatocracy, and the continued erosion of our personal digital freedom.