Movie review by Greg Carlson

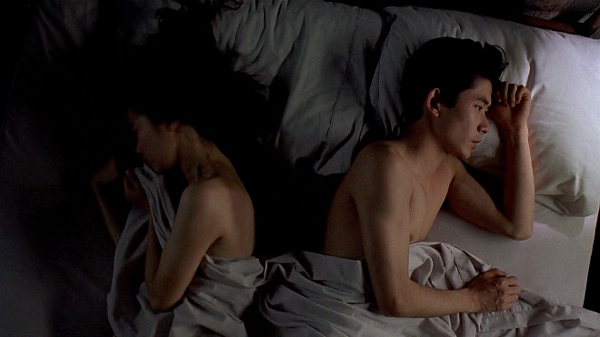

A dizzying whirlwind of cinematic sensory overload, Gyorgi Palfi’s “Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen” demands the attention of every serious movie lover besotted with the woozy power of the silver screen. Lyrically edited from more than 450 films – some bad, many good, several great – Palfi’s achievement is undeniable once the lights go down and the journey begins. “Final Cut” is reflexive film construction par excellence, crafting a coherent narrative from dozens of reliable visual tropes tumbling and cascading to form a celluloid romance that makes the viewer the third member of an irresistible ménage a trois. Relying on the alchemy of a quartet of credited editors whose names few Americans will recognize, Palfi’s “film for educational purposes” will very likely exist in the legal shadows for some time to come.

In the post-YouTube era, the supercut has emerged as one of the most delectable bonbons of remix culture. According to the Wikipedia entry on the phenomenon, the term was coined in a 2008 blog post attesting to, as Andy Baio put it, the “genre of video meme, where some obsessive-compulsive superfan collects every phrase/action/cliche from an episode (or entire series) of their favorite show/film/game into a single massive video montage.” Movie-derived supercuts serve, among other things, to point out the numbing shorthand that wallpapers scripts struggling to achieve novelty – but can also be easily purposed for simultaneous critique and celebration.

For example, London-based supercut maestro Harry Hanrahan stictches together insanely gratifying mash-ups including “It’s Showtime!” and “Get Out of There!” as well as reels of heroes and villains getting hit by buses, Julianne Moore crying, Sean Bean dying, and Nicolas Cage losing his shit. Jonny Wilson’s Eclectic Method project presents a series of mind and ear-bending collages, including “mixtapes” featuring the work of directors like Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, Pedro Almodovar, and John Hughes. Baio and Michael Bell-Smith launched Supercut.org as a repository for the work of obsessive compilers.

When it was added to the 50th anniversary schedule of the New York Film Festival in 2012, the program notes opened with the claim that “Final Cut” was “an odds-on candidate for the greatest movie ever made,” and as metanarratives go, that hyperbole doesn’t feel so far from the mark. At 85 minutes, however, “Final Cut” doesn’t measure up to the Incredible Hulk-like muscle of one of its closest siblings, Christian Marclay’s unbelievable installation project “The Clock” (2010), a monumental 24-hour marathon that synchronizes the moments of the day with corresponding shots from popular movies.

“Final Cut,” “The Clock,” and to some degree even Thom Andersen’s crazy ambitious 2003 documentary “Los Angeles Plays Itself” allow – maybe even encourage and invite – the spectator to an individualized experience. In his “Final Cut” review, Paul Constant notices the seemingly large number of clips from “Dick Tracy” and “Sin City.” I couldn’t help but alight on the love Palfi shows for Alan Parker’s 1987 cult favorite “Angel Heart.” There is plenty of Hitchcock. And it is impossible to ignore Palfi’s affinity for David Lynch, whose images are featured prominently along with a few choice sound and music cues, including Angelo Badalamenti’s “Twin Peaks” theme.

Music is, not surprisingly, of tremendous importance in an endeavor like “Final Cut,” which depends very little on spoken dialogue to propel forward its action. It all opens to Alan Silvestri’s main title from “Back to the Future,” a perfect choice given the ability of “Final Cut” to transport audience members shot-to-shot through space and time, from the silent era to contemporary CGI-dependent blockbusters. Michael J. Fox’s Marty McFly will shortly remark “This has gotta be a dream,” echoing the thoughts of most giddy viewers. The Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” plays underneath a series of leading men on the move, skipping from Travolta’s strut to “Oldboy” to “Closely Watched Trains” to “Ninotchka” and so on.

On Twitch, Joshua Chaplinsky and Peter Gutierrez disagreed about the effectiveness of the movie’s boy-meets-girl device, with Gutierrez dismissing what he reads as an “intentionally simplistic” story that “ultimately doesn’t take the audience anywhere new or truly unexpected.” Chaplinsky counters that the “technical complexity of the experiment only benefits from the simplicity of the narrative,” going on to claim that “cinema is romance.” While I tend to side with Chaplinsky, one’s mind automatically begins to imagine roads untraveled by Palfi, since so much of the power of “Final Cut” resides in the rhymes of the edits. Here’s hoping more dreamers will pick up the torch.